I have been collecting anthologies of postwar piano music. They are often interesting because they show the publishers’ and editors’ sense of what counted, at any given moment, as the most advanced music that was also marketable. Each is the result of decisions about where to begin (Reger? Fauré? Schönberg? Debussy?), what styes and generations to include, where to end, and what counts as “new,” “contemporary,” or “experimental.” In those respects these anthologies are like history textbooks, with samples rather than text.

For example there’s the amazing series Neue Klaviermusik aus europäischen Ländern, which appeared first in 1965: the volumes that represent Soviet-bloc countries are full of folk music and easy-to-intermediate pieces; the volumes that represent western Europe are stocked with especially astringent modernism. Or there’s The International Library of Piano Music, which appeared in 1967, and had a large editorial board including Leonard Bernstein, Roger Sessions, and several pianists: it’s a perfect snapshot of postwar America, with a didactic chapter on modern music techniques written by an exponent of the Vienna school, but it carefully balances its homages to Stravinsky and Schönberg. Some anthologies are remarkably ideologically consistent: the UE-Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts is virtually a textbook on the Vienna school and Darmstadt, with little patience for anything else.

Each has its flavor, and plays (or reads) like a report of its immediate cultural context. Several would make excellent short programs for performance! I have included some ideas along that line.

This is a fairly exhaustive list; at the moment there are about 20 entries. I’d be glad to receive corrections and additions. It’s difficult to know how many more anthologies there are, because they’re hard to search. I have looked using Google, used.addall, the various national Amazons, WorldCat, eBay, and sheetmusicplus. There must be a lot missing: I have no French, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, or Spanish anthologies. Please let me know about omissions and errors. Thanks!

The list begins in 1940, and goes in chronological order by year of first publication. I have written comments on about a quarter of these; I intend to add more notes, perhaps in separate posts, if this page gets too big.

1940

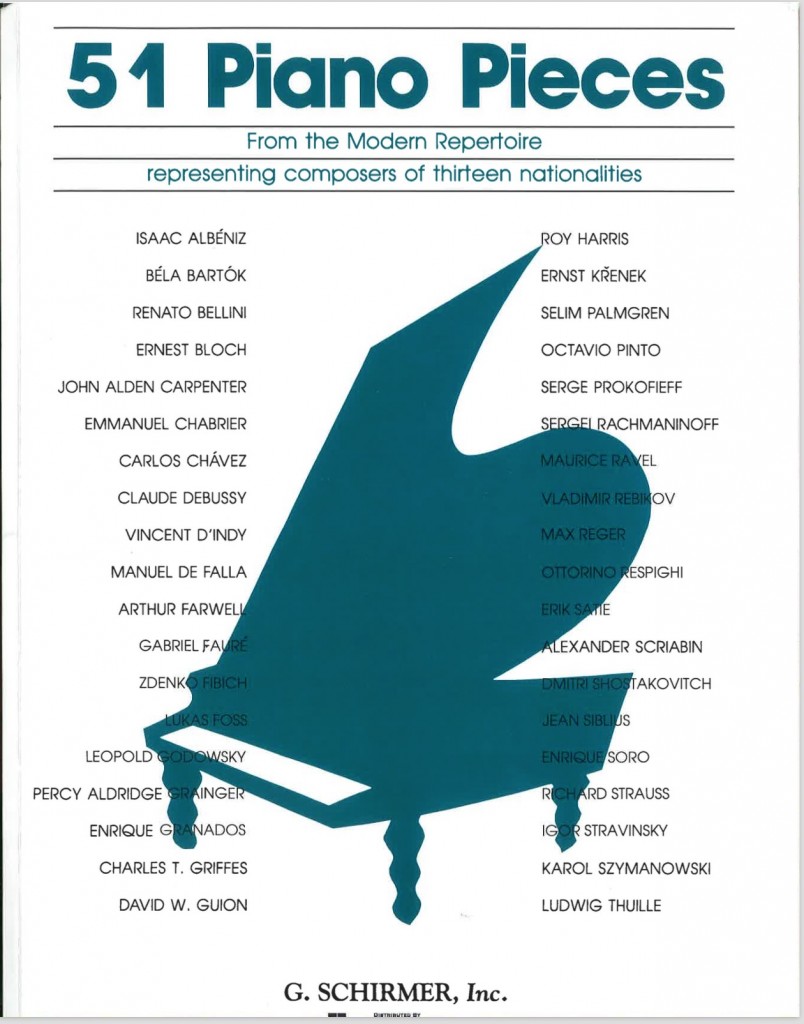

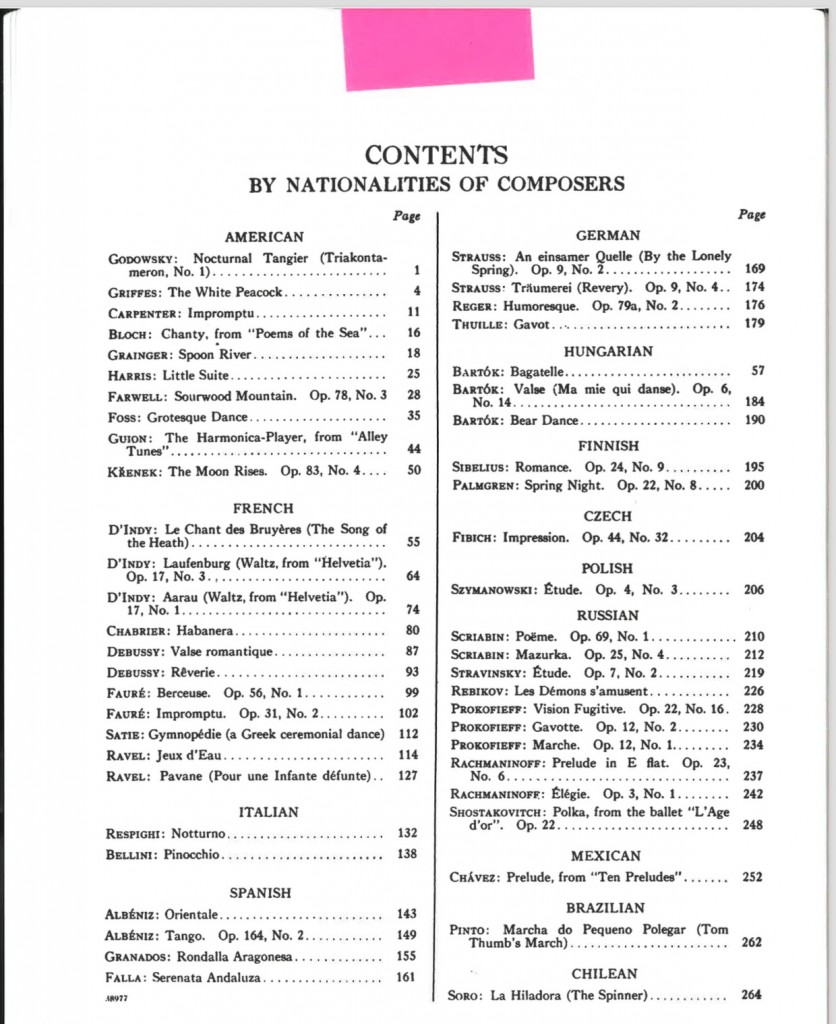

51 Piano Pieces From the Modern Repertoire: Representing Composers of Thirteen Nationalities (Schirmer, 1940)

This is a good starting place for post-war anthologies because it is a resumé of stock pieces of the popular salon literature of the first half of the century, with a couple of anomalous avant-garde pieces thrown in to ensure it appeared up-to-date.

This is a good starting place for post-war anthologies because it is a resumé of stock pieces of the popular salon literature of the first half of the century, with a couple of anomalous avant-garde pieces thrown in to ensure it appeared up-to-date.

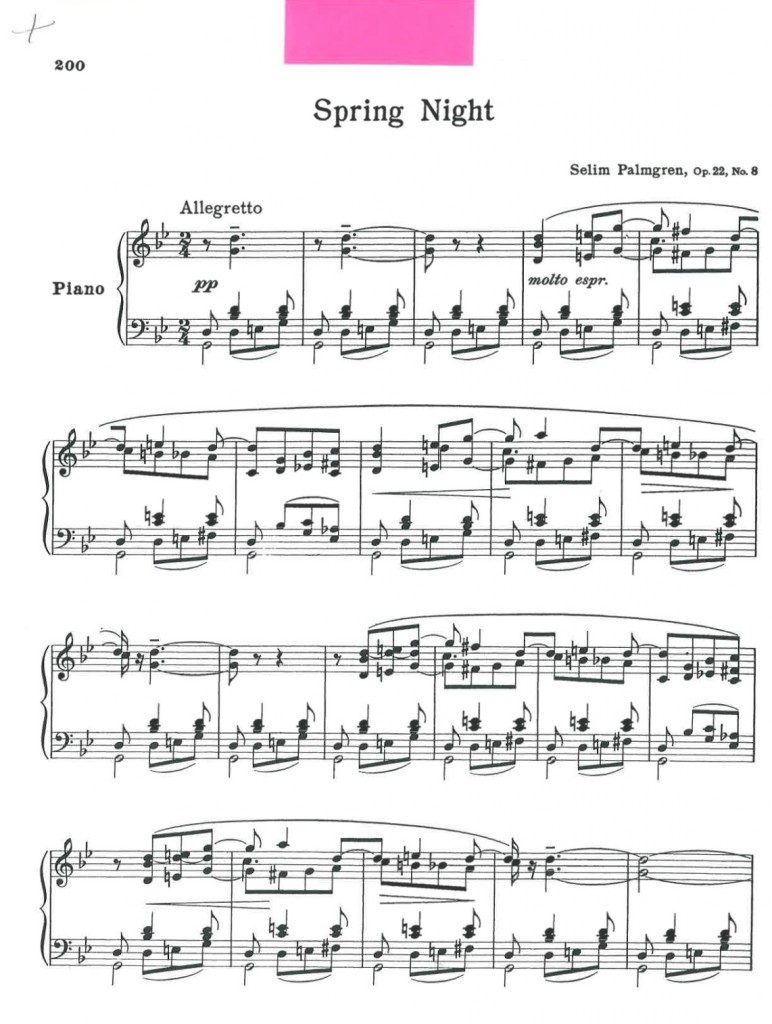

The salon literature includes Percy Grainger’s Spoon River, pieces by Granados and Albéniz, Debussy’s Rêverie, and the Brazilian composer Octavio Pinto‘s Tom Thumb’s March, Rachmaninoff’s Élégie Op. 3 no. 1 and Prelude in E flat Op. 23 no. 6, and Emmanuel Chabrier’s Habanera. Some of these are showpieces, requiring advanced technique. (There are also some less familiar salon pieces here, several of which are rewarding: Fauré’s Berceuse, Ottorino Respighi’s Nottorno, Richard Strauss’s An einsamer Quelle Op. 9 no. 2, and “the Finnish Chopin” Selim Palmgren‘s Spring Night Op. 22 no. 8.)

The anthology is organized according to nationality, and it’s striking that the few dissonant compositions are by Americans or composers living in America: Roy Harris’s Little Suite and Ernst Křenek’s The Moon Rises. There are also the obligatory pieces by Bartók, but nothing from the Vienna school: the European avant-garde is represented by Richard Strauss and Scriabin, especially the exemplary late Poëme Op. 69 no. 1, which stands in for the late sonatas.

The anthology is organized according to nationality, and it’s striking that the few dissonant compositions are by Americans or composers living in America: Roy Harris’s Little Suite and Ernst Křenek’s The Moon Rises. There are also the obligatory pieces by Bartók, but nothing from the Vienna school: the European avant-garde is represented by Richard Strauss and Scriabin, especially the exemplary late Poëme Op. 69 no. 1, which stands in for the late sonatas.

Shostakovich’s Polka from l’Age d’or is included, no doubt as a “grotesque” piece (Lukas Foss’s Grotesque Dance is also here), without any awareness of Shostakovich’s bitterness or irony.

Shostakovich’s Polka from l’Age d’or is included, no doubt as a “grotesque” piece (Lukas Foss’s Grotesque Dance is also here), without any awareness of Shostakovich’s bitterness or irony.

1945 (ca.)

36 Twentieth-Century Piano Pieces: A Collection of Contemporary Works for Recital and Study (Schirmer, n.d., c. 1945)

This is one of the most versatile American anthologies. It is regionalist and populist, but also contemporary (many pieces were composed within five years of publication), so it represents mid-twentieth century North American taste quite well.

This is one of the most versatile American anthologies. It is regionalist and populist, but also contemporary (many pieces were composed within five years of publication), so it represents mid-twentieth century North American taste quite well.

It begins by acknowledging a certain French tradition, with Gabriel Fauré’s very playable Clair de lune. I assume Fauré provided a politic starting place, enabling the anthologist to avoid both the German and Russian schools, and even to sidestep the route to modernism offered by the route from Debussy through Messiaen to Boulez—who would have been very much on some American composers’ minds in 1945.

Most of the composers here are American: Edward MacDowell, William Schuman, the Chicagoans John Alden Carpenter and Robert Muczynski, Samuel Barber, Paul Creston, Norman Dello Joio (represented by a lovely piece in octave ostinato, the third movement of the Suite for Piano, 1945), and Irving Fine. There are also a number of Anglophone composers, such as the Australian Percy Grainger, the Swiss-born Ernest Bloch, Ernst Křenek, and Cyril Scott (represented by the excellent Lento). A token Hispanic presence is also typical for mid-century American anthologies: here it’s the Mexican composer Carlos Chávez.

There are unusual choices throughout: Ernest Bloch’s Waves (1923) is a good set piece, whose dissonances complement the opening Fauré; there is also William Schuman’s Three-Score Set (1943), and Irving Fine’s very well-balanced Prelude from Music for Piano (1949), which shows why Stravinsky made him an exemplar. (I will write about Fine’s music in a separate post.) The anthology also has Leonard Bernstein’s Four Anniversaries (1948), which show the influence of both Stravinsky and Copland.

1948

Das neue Klavierbuch, edited by Willi Drahts and Friedrich Zehm (Schott, 1948).

This was first published in the U.S. in 1961, according to WorldCat, so it would have been received very differently than in Germany in 1948. The original publication date suggests it would have been known in Darmstadt; the North American publication date suggests it could have been seen at Princeton.

This was first published in the U.S. in 1961, according to WorldCat, so it would have been received very differently than in Germany in 1948. The original publication date suggests it would have been known in Darmstadt; the North American publication date suggests it could have been seen at Princeton.

There is a publication puzzle here. Currently this anthology is 3 volumes. (Volume 2 of the 2014 printing is shown above.) This is what I assume: the original 1948 publication was one volume, and

contained the current volumes 1 and everything in volume 2 except the final piece. The final piece of volume 2 was copyrighted in 1951, and so are the opening pieces in volume 3. So I assume those were additions made sometime around 1953. Then the current, three-volume series would have been done around 1983 and not subsequently revised; I review it separately under that date.

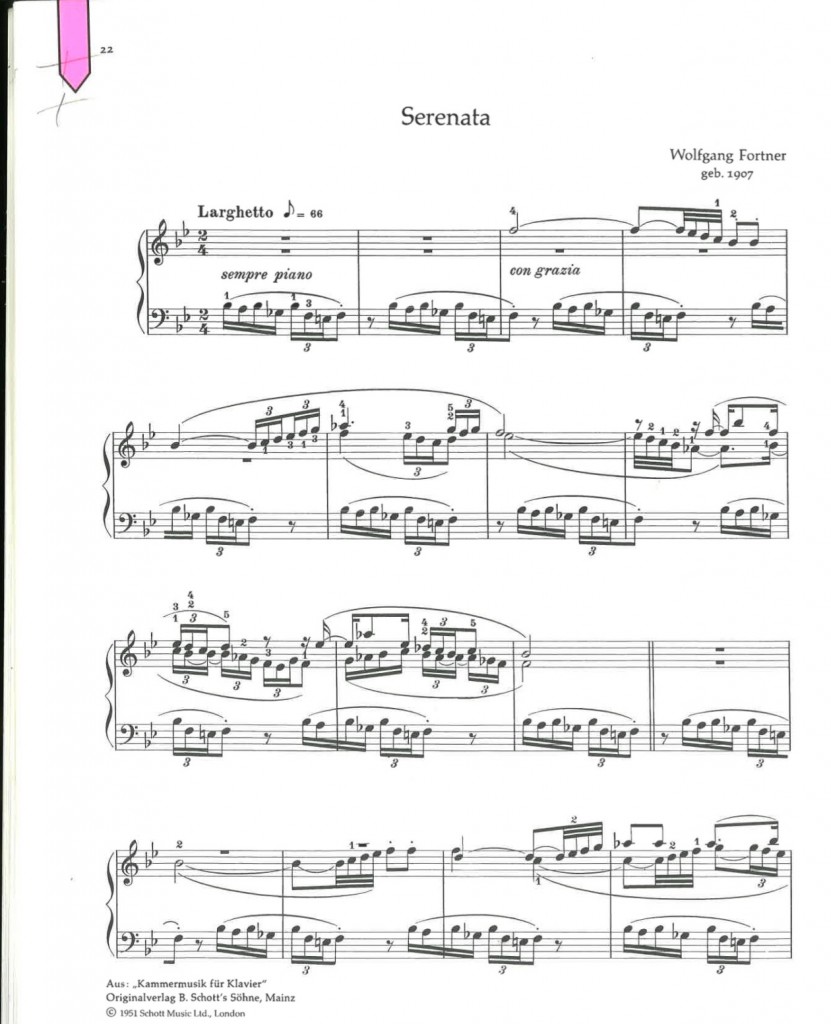

Volume 1 is limited by its purview: it includes only “leichte Klavierstücke zeitgenössischer Komponisten.” Even so, the editors found some rewarding pieces: Wolfgang Fortner‘s Serenata and Lied (1951, see below), the Dutch composer Henk Badings‘s Air from his Reihe kleiner Klavierstücke, and Wilhelm Maler‘s Drei kleine Stücke (1948). The tone is set for vol. 1 by the opening piece, Hindemith’s Marsch.

Volume 2 is a serious selection of works mainly from the 1920s, with a couple from the 1940s. It opens with the Volkslied from Bartók’s Zehn leichte Klavierstücke, unusually simple piece. It would be interesting to know why it was chosen: perhaps its bareness made it less liable to be associated with the “bad” ethnographer and folk-musician Bartók, but also not exclusively with the “good” dissonant, percussive composer of the Fourth String Quartet and the Piano Sonata.

Volume 2 is a serious selection of works mainly from the 1920s, with a couple from the 1940s. It opens with the Volkslied from Bartók’s Zehn leichte Klavierstücke, unusually simple piece. It would be interesting to know why it was chosen: perhaps its bareness made it less liable to be associated with the “bad” ethnographer and folk-musician Bartók, but also not exclusively with the “good” dissonant, percussive composer of the Fourth String Quartet and the Piano Sonata.

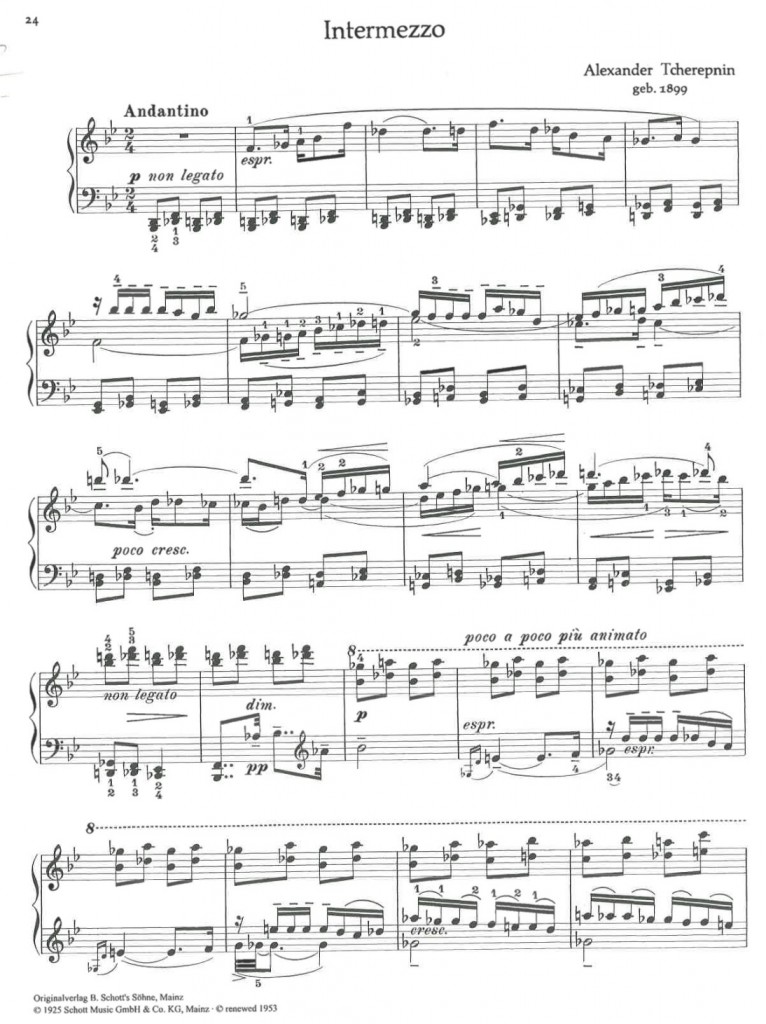

After the Bartók comes a Sonatine by Boris Blacher. Pride of place is given in vol. 2 to Hindemith; the French school is represented by Milhaud, Françaix—the wonderful La tendre—and Poulenc, and there is also a piece by Tcherepnin, Intermezzo.

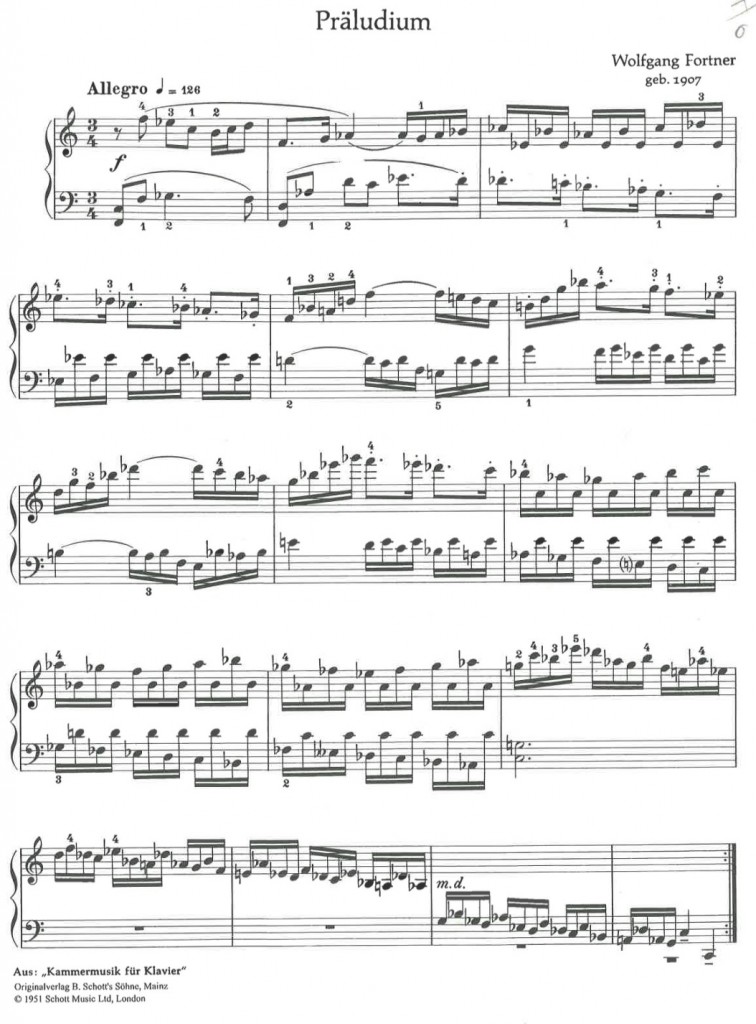

The last piece in vol. 2 is a Bach-inspired neoclassical Prelude by Wolfgang Fortner, copyrighted 1951—i.e., after the initial publication date of 1948, and therefore presumably part of an augmented edition that I’m assuming was published sometime around 1953.

The other pieces that would have been added around 1953 are in the opening of volume 3, which begins with three more German pieces: Hindemith’s In einer Nacht and Rufe in der horchenden Nacht, and another piece by Fortner—but after those pieces, volume 3 turns suddenly to America (Copland’s Sentimental Melody), France (Françaix’s En cas de succès), and Italy (Ligeti’s Lamento from the early Musica Ricercata, a typically thundering Bartókian piece). If these are in fact additions made around 1953, then the choices make perfect sense: it would have been almost ten years after the Second World War, and the anthology was made more international.

(Notes on volume 3 continue below, under the assumed publication date of 1983.)

1951

The UE Piano Book (Universal Edition).

This was published for the 50th anniversary of Universal Edition. See remarks under UE-Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts (1968)—that is an expanded version of this book.

1956 (ca.)

Contemporary British Piano Music (Schott and Co.)

This is a small anthology, with only four composers represented: the Australian Don Banks, Peter Racine Fricker, the Scot Iain Hamilton, and Humphrey Searle. In the edition I have (presumably a reprint) the notes are uncomfortably small and the pages are poorly printed.

1964

The World of Modern Piano Music, edited by Denes Agay (MCA, 1964).

This is subtitled “Easy, Original Pieces by Contemporary Composers”; the composers’ birth dates range from the 1880s (Bartók, Marion Bauer, Ernst Toch) to the 1920s (Robert Starer, Yoshinao Nakada).

This is subtitled “Easy, Original Pieces by Contemporary Composers”; the composers’ birth dates range from the 1880s (Bartók, Marion Bauer, Ernst Toch) to the 1920s (Robert Starer, Yoshinao Nakada).

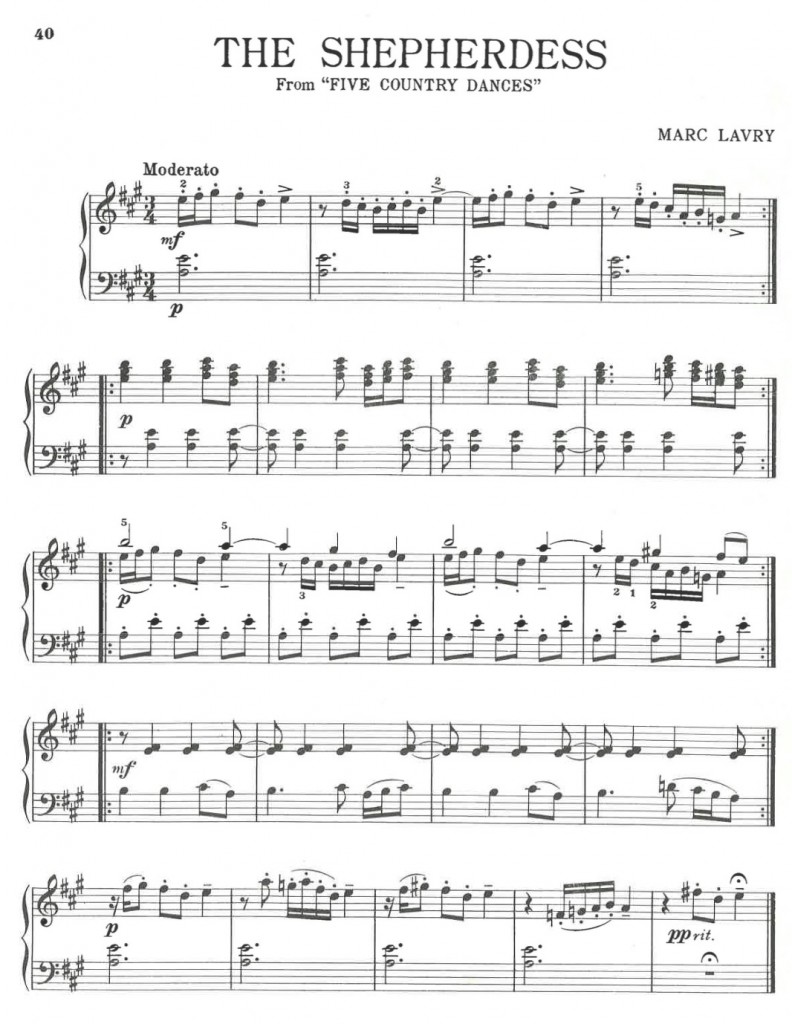

The Israeli composer Marc Lavry (1903-1967) is represented by two pieces:

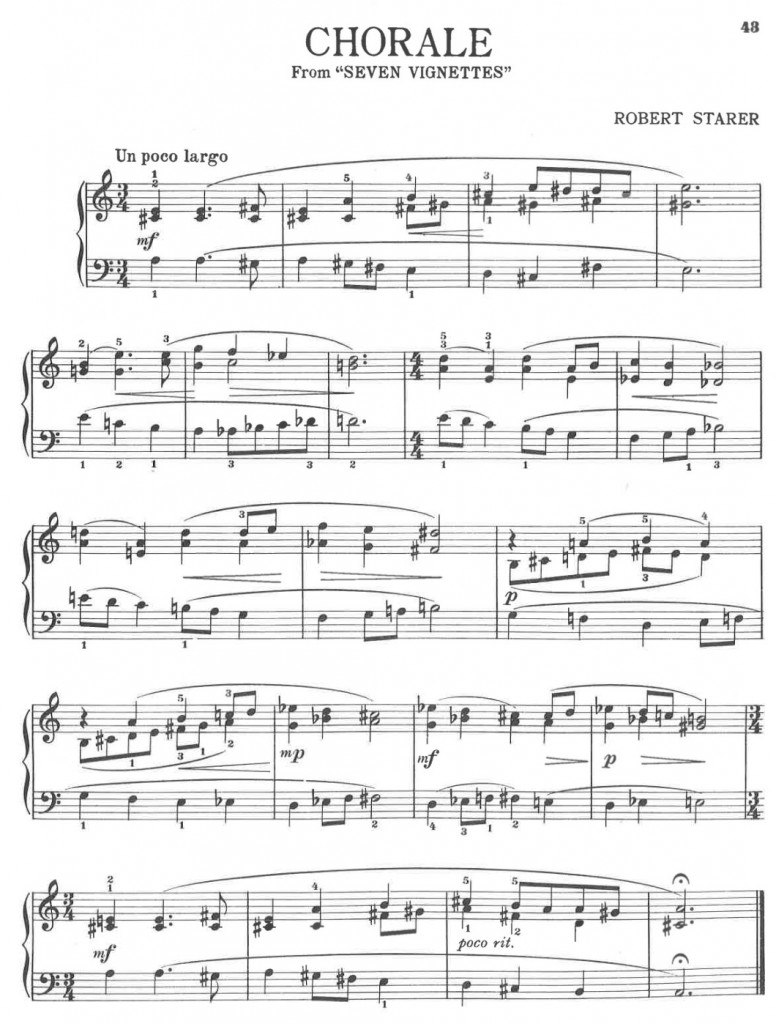

The Austrian-born American composer Robert Starer (1924-2001) is represented by two pieces, one of them a chromatically inventive Chorale:

The Austrian-born American composer Robert Starer (1924-2001) is represented by two pieces, one of them a chromatically inventive Chorale:

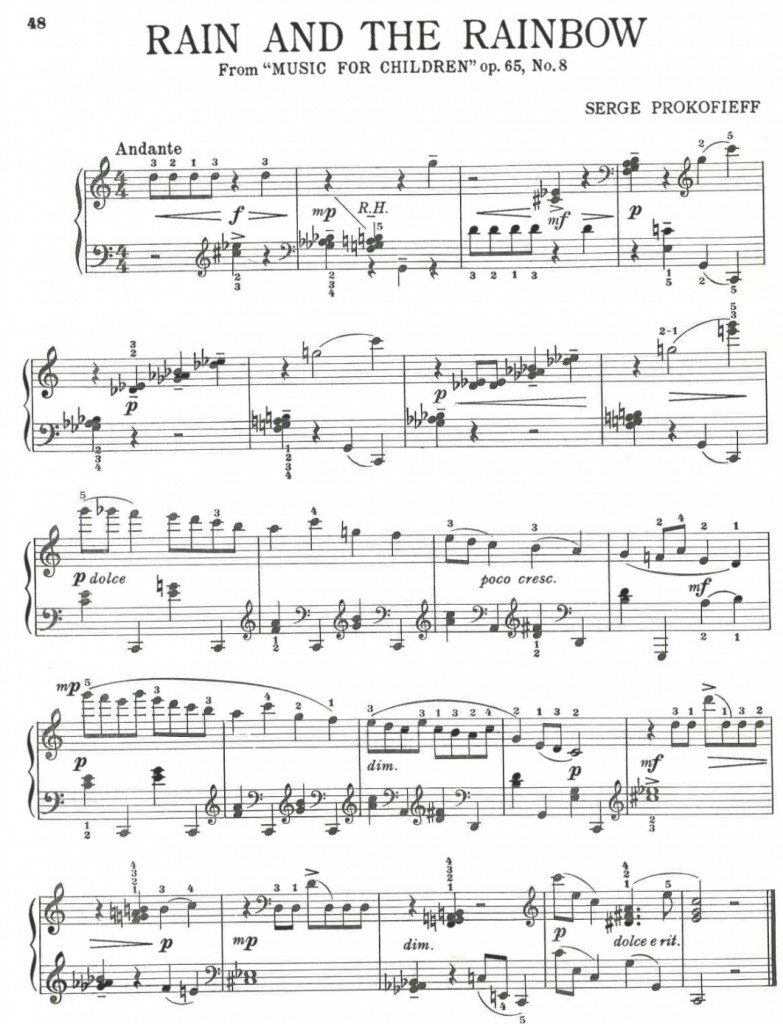

This anthology also includes some less-often anthologizes Prokofiev and Bartók pieces, such as Prokofiev’s Bartókian Rain and the Rainbow:

1965

Neue Klaviermusik aus europäischen Ländern / Contemporary Piano Music from European Countries (Hans Gerig, 1965 et seqq.). One of these is discussed in some detail elsewhere on this site.

This series is one of the most obscure twentieth-century anthologies of piano music. Even with addall.com and amazon, it is nearly impossible to find some of the titles. There are some very obscure titles and composers, and the series has a complex publishing history. It’s harder than usual to collect because most, or all, were issued in 2 vols., and they have become separated. (I have marked the ones I have not seen.) Does anyone know what the full list of countries is? Was Neue Sowjetische Klaviermusik ever published? Anyone find it on the internet? It’s strange to have such puzzles in this day and age.

This series is one of the most obscure twentieth-century anthologies of piano music. Even with addall.com and amazon, it is nearly impossible to find some of the titles. There are some very obscure titles and composers, and the series has a complex publishing history. It’s harder than usual to collect because most, or all, were issued in 2 vols., and they have become separated. (I have marked the ones I have not seen.) Does anyone know what the full list of countries is? Was Neue Sowjetische Klaviermusik ever published? Anyone find it on the internet? It’s strange to have such puzzles in this day and age.

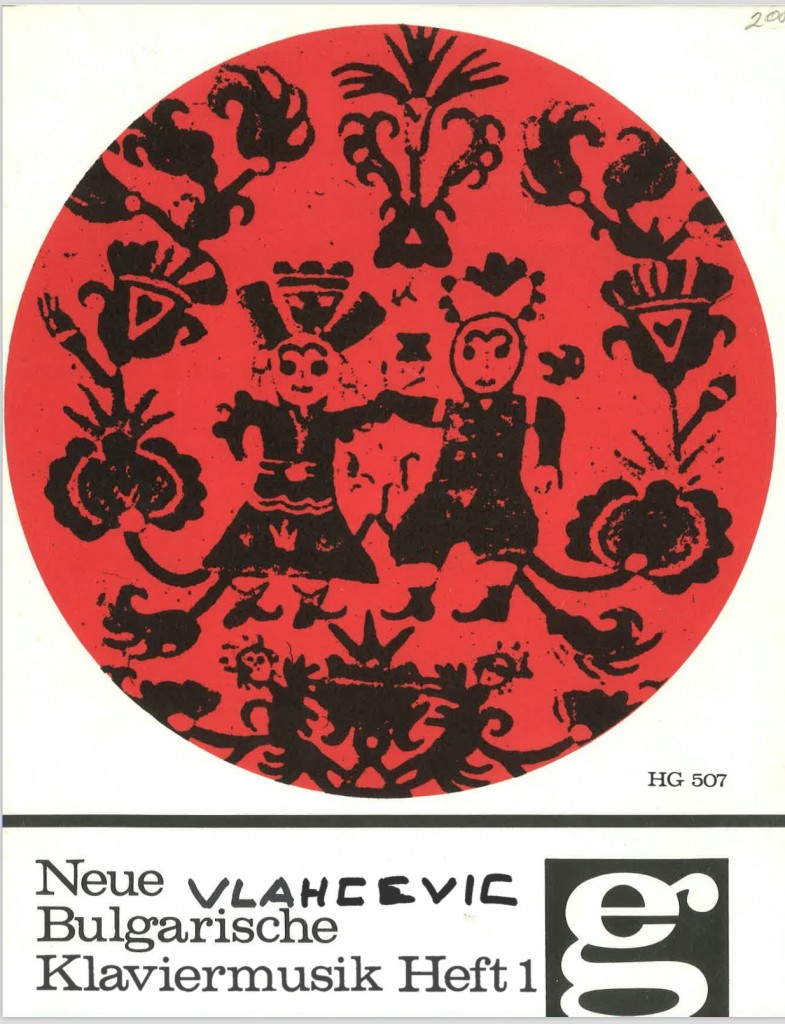

One of the principal features of this series is the strong contrast between Soviet-bloc volumes and others. In the Bulgarian and Romanian volumes, for example, the music is Soviet-approved, with folk themes and a general absence of virtuosity. In some other volumes there has been an attempt to showcase the most “difficult” recent music.

(A) Neue Griechische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Günther Becker. Volume 1 is generally excellent, with unfamiliar works and composers influenced by Bartók, Stockhausen, Shostakovich, Poulenc, and Prokofiev. Nikos Skalkottas is represented by the Little Peasant March from the 32 Piano Pieces; there are also pieces by Yorgo Sicilianos, Stephanos Gazouleas, Yannis Papaioannou, and Michael Adamis.

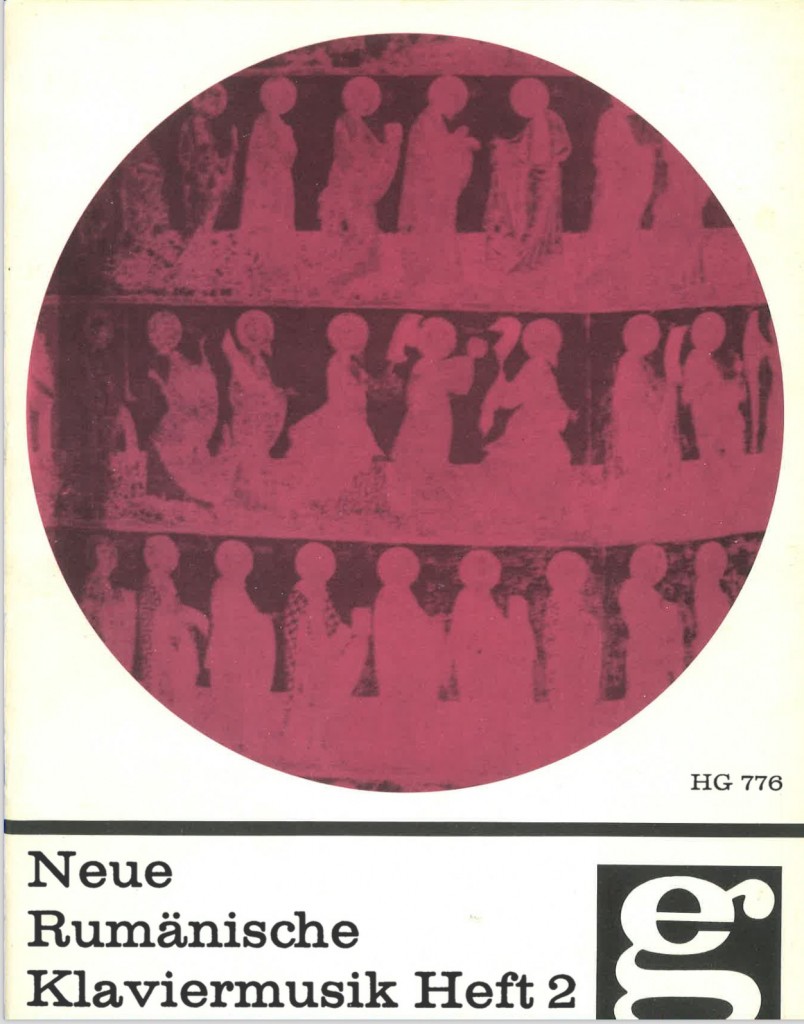

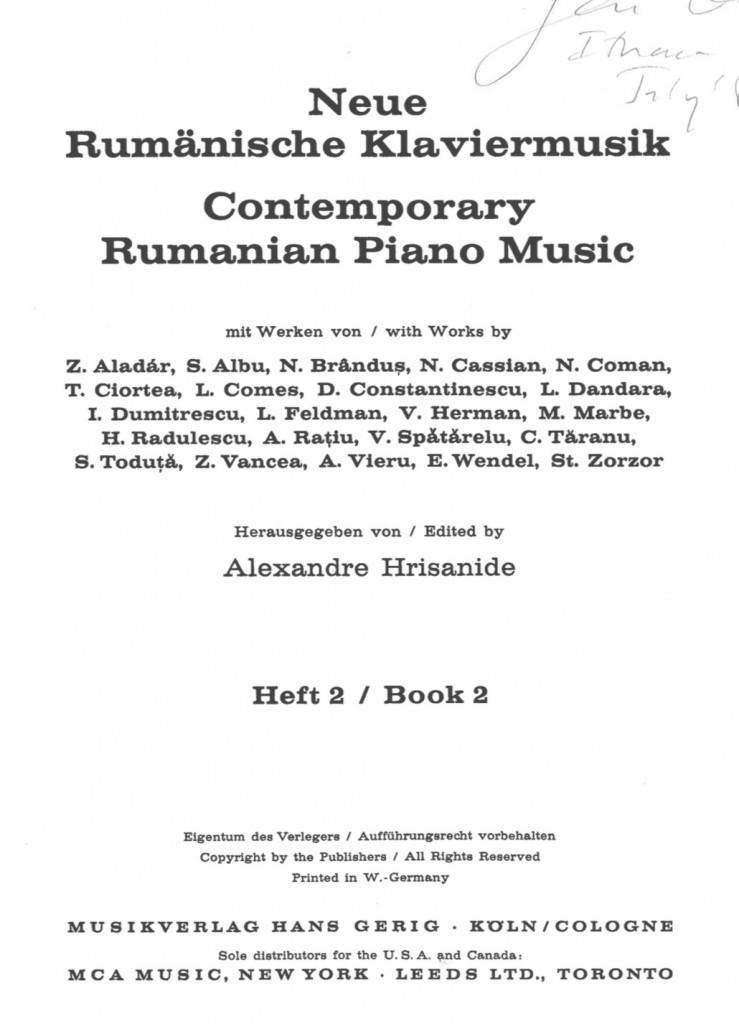

(B) Neue Rumänische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Aledandre Hrisanide.

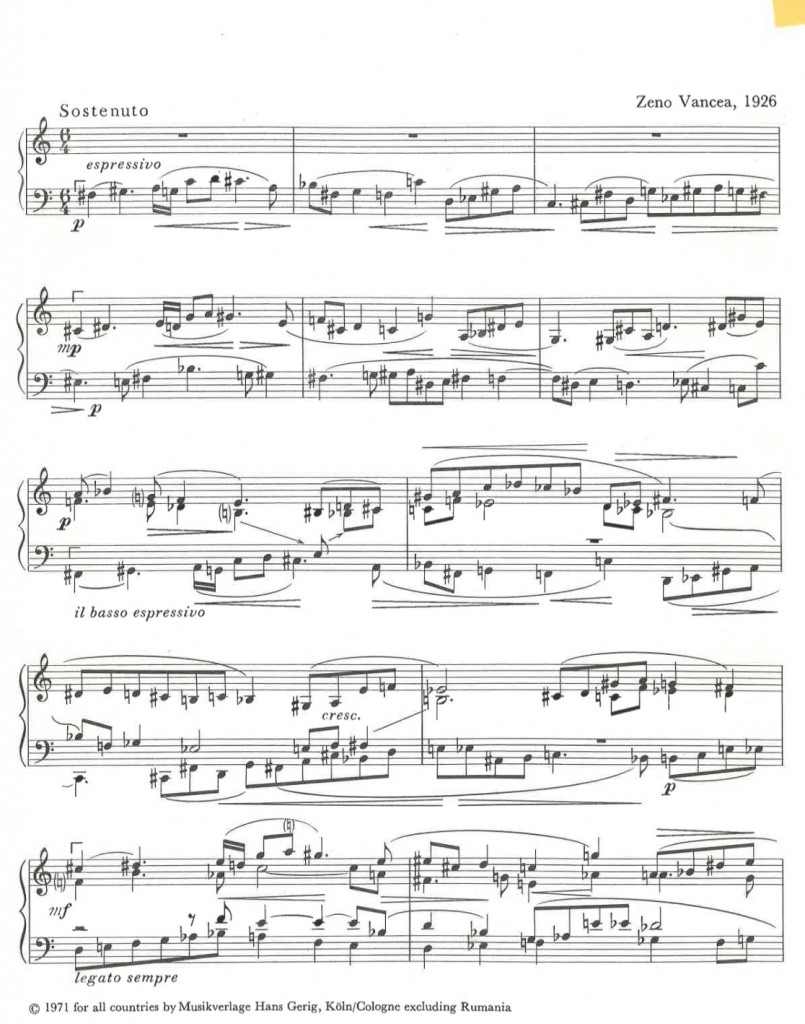

The first volume is discussed in another post. Volume 2 also has some outstanding pieces, especially a thoughtful slow three-part fugue by Zeno Vancea:

The first volume is discussed in another post. Volume 2 also has some outstanding pieces, especially a thoughtful slow three-part fugue by Zeno Vancea:

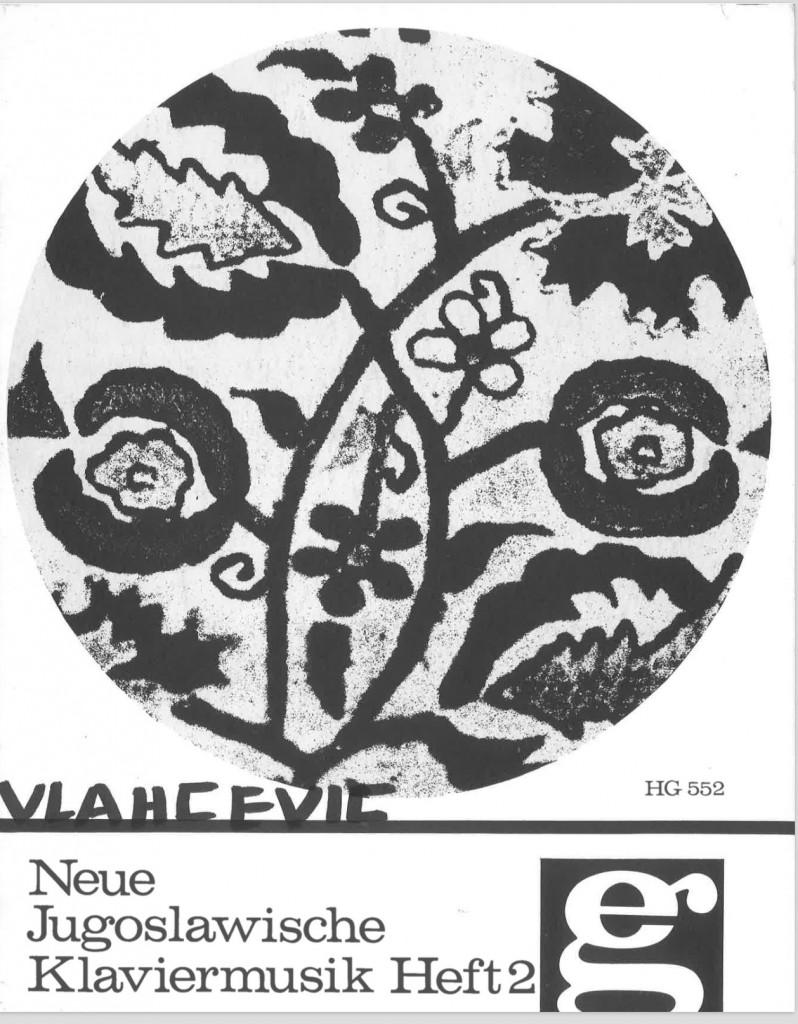

(C) Neue Jugoslawische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Rudolf Lück.

Volume 1 is a collection of pieces heavily influenced by Bartók, and mainly at the level of Mikrokosmos volume 3. An exception is Božidar Kunc’s (1903-1964) Draga priča (The Favorite Fairy Tale), which owes its harmonies to Debussy.

Volume 1 is a collection of pieces heavily influenced by Bartók, and mainly at the level of Mikrokosmos volume 3. An exception is Božidar Kunc’s (1903-1964) Draga priča (The Favorite Fairy Tale), which owes its harmonies to Debussy.

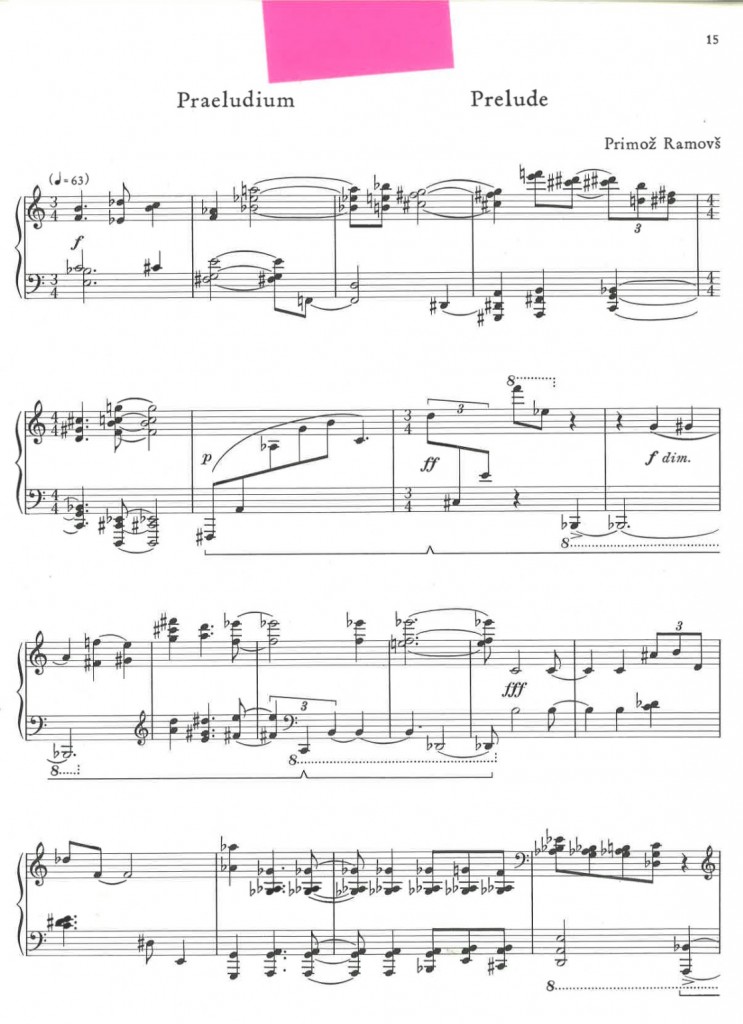

There is some strongly dissonant music in volume 2, influenced by the Viennese school. Primož Ramovš’s Prelude, for example, is determinedly atonal.

In the Introduction, Rudolf Lück dates the inception of modernism to the Muzicki Biennale in Zagreb in 1961, although he also notes that “this influence has been mostly restricted to composers of northern Yugoslavia.” Volume 2 ends with the most difficult piece, Dialogue by Ivo Malec, which shows the influence of Stockhausen (Malec has also been compared to Xenakis).

In the Introduction, Rudolf Lück dates the inception of modernism to the Muzicki Biennale in Zagreb in 1961, although he also notes that “this influence has been mostly restricted to composers of northern Yugoslavia.” Volume 2 ends with the most difficult piece, Dialogue by Ivo Malec, which shows the influence of Stockhausen (Malec has also been compared to Xenakis).

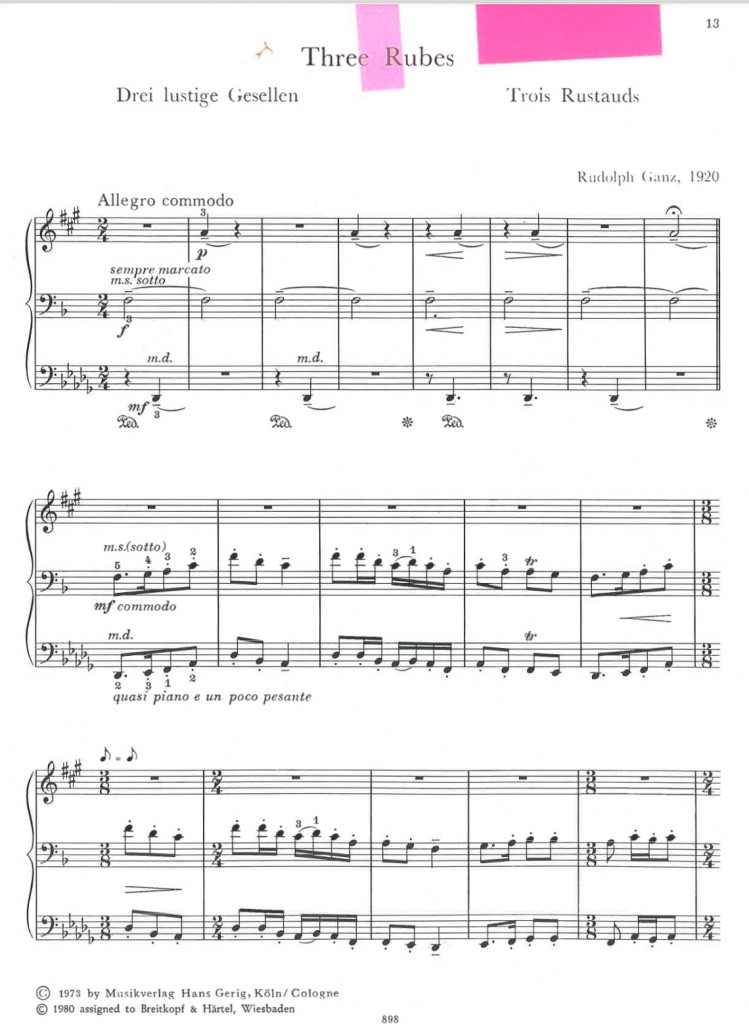

(D) Neue Schweizerische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Charles Dobler.

I have vol. 1; I can’t find vol. 2. Highlights here include Rudolph Ganz‘s Three Rubes (1920), which is written on three staves, each with a different key signature (see the scan below); Roger Vuataz‘s Question-Response (1968), which is written in a compound meter (“2/4 3/4 4/4”); and Hugo Pfister’s Crystallizations (1968).

I have vol. 1; I can’t find vol. 2. Highlights here include Rudolph Ganz‘s Three Rubes (1920), which is written on three staves, each with a different key signature (see the scan below); Roger Vuataz‘s Question-Response (1968), which is written in a compound meter (“2/4 3/4 4/4”); and Hugo Pfister’s Crystallizations (1968).

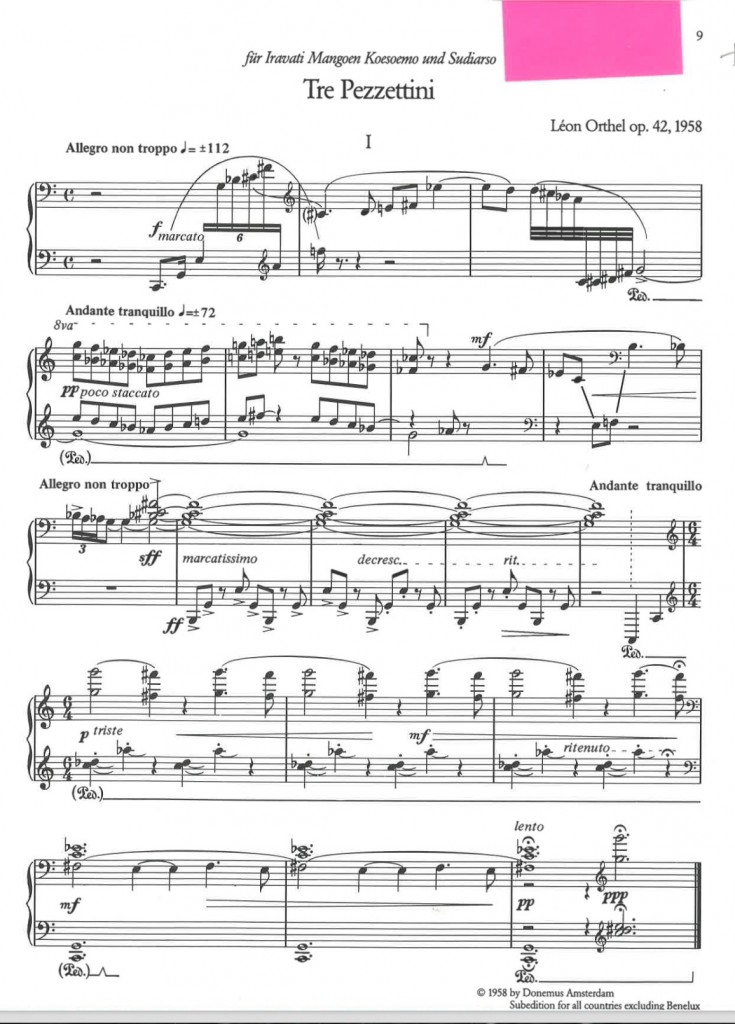

(E) Neue Niederländische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Ton Hartsuiker.

I have vol. 2; I can’t find vol. 1. In contrast to the Soviet-bloc volumes, this is full of spiky avant-garde compositions, by Peter Schat, Otto Ketting, Léon Orthel (below), Hans Kox, and others.

I have vol. 2; I can’t find vol. 1. In contrast to the Soviet-bloc volumes, this is full of spiky avant-garde compositions, by Peter Schat, Otto Ketting, Léon Orthel (below), Hans Kox, and others.

There is even a double-page fold-out: Daan Manneke‘s Polychroon (1978); it makes me wonder if the Dutch government helped subsidize this volume.

There is even a double-page fold-out: Daan Manneke‘s Polychroon (1978); it makes me wonder if the Dutch government helped subsidize this volume.

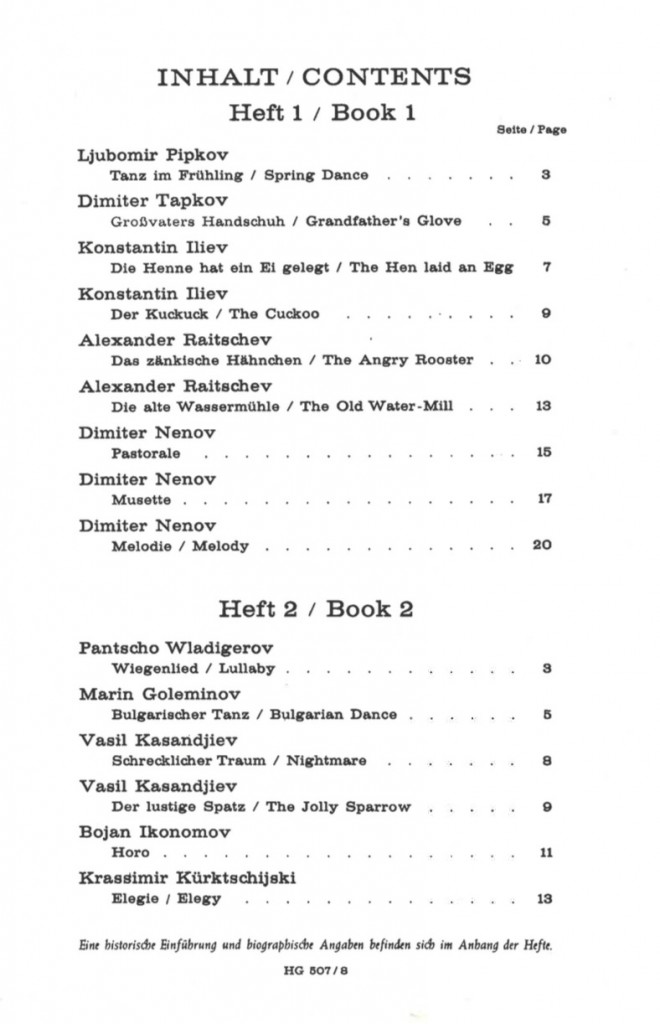

(F) Neue Bulgarische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Otto Daube. This is another two-volume set that is mainly Soviet-approved material, so it’s heavy on folk music and harmless or wholesome narrative themes, and there is a relative absence of technically difficult music. There are several good pieces for beginning pianists in volume 1, such as Konstantin Iliev‘s The Hen Laid an Egg, Alexander Raitschev’s The Angry Rooster, and Dieter Nenov‘s Melody. Volume 2 also has a couple of wonderful pieces: a disconsolate, lyrical and dissonant Lullaby by the very skilled composer Pantscho Wladigeroff (Pancho Kharalanov Vladigerov; he is also represented in the UE-Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts, published in 1968), and an Elegy by Krassimir Kürktschijski.

This is another two-volume set that is mainly Soviet-approved material, so it’s heavy on folk music and harmless or wholesome narrative themes, and there is a relative absence of technically difficult music. There are several good pieces for beginning pianists in volume 1, such as Konstantin Iliev‘s The Hen Laid an Egg, Alexander Raitschev’s The Angry Rooster, and Dieter Nenov‘s Melody. Volume 2 also has a couple of wonderful pieces: a disconsolate, lyrical and dissonant Lullaby by the very skilled composer Pantscho Wladigeroff (Pancho Kharalanov Vladigerov; he is also represented in the UE-Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts, published in 1968), and an Elegy by Krassimir Kürktschijski.

(Information on these composers can be found on the Union of Bulgarian Composers’ website, often under alternate transliterations.)

(G) Neue Skandinavische Klaviermusik, edited by Herbert Connor. In one volume. This is marked “Not available for U.S.A. and Canada.”) I can’t find this online.

(H) Neue Sowjetische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Rudolf Lück. I can’t find this online.

(I) Neue Tschechoslowakische Klaviermusik, in 2 vols., edited by Jan Matejček. I can’t find this online.

There were apparently more titles, perhaps published by Breitkopf as a continuation of the Gerig series?

(J) Neue Deutsche Klaviermusik, in 2 vols. I have not seen either volume. Strange this one should be so rare: the Romanian, Yugoslavian, and Bulgarian volumes appear from time to time on the internet, but I haven’t seen this yet. I wonder if the Balkan volumes were given larger initial print runs.

(K) Neue Brasilianische Klaviermusik, edited by Paulo Affonso de Moura Ferreira, 1978. I haven’t seen this either; I don’t know if it appeared, or if it was also 2 vols., or if it was planned as part of a Latin American expansion of the series.

I think all the books would be in Classical Keyboard Music in Print (1993). I hope to post more on individual volumes in future.

1967

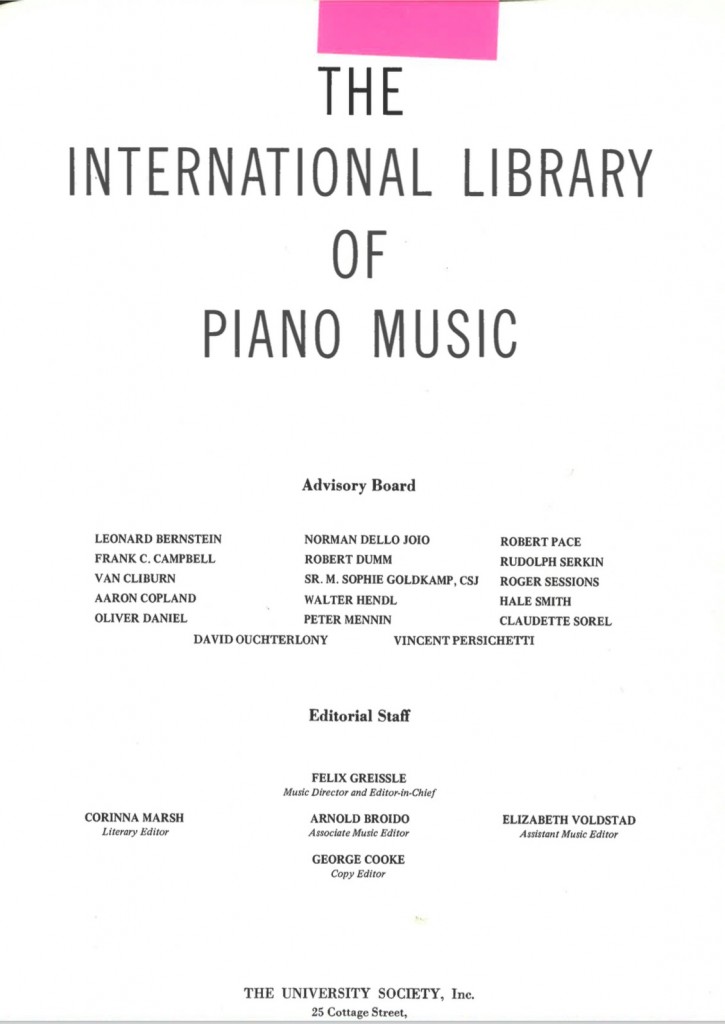

The International Library of Piano Music, edited by Felix Greissle et al., in 16 “Albums,” “Album” (volume) 9 (The University Society, 1967–1973).

This is a fascinating anthology. It is the final volume of a series of piano music; the title page lists an Editorial Staff of 4 and an Advisory Board of 17, including Leonard Bernstein, Vincent Persichetti, Van Cliburn, Norman Dello Joio, Roger Sessions, Rudolph Serkin, and Aaron Copland. My copy is a hardbound volume with over 150 pages of music.

This is a fascinating anthology. It is the final volume of a series of piano music; the title page lists an Editorial Staff of 4 and an Advisory Board of 17, including Leonard Bernstein, Vincent Persichetti, Van Cliburn, Norman Dello Joio, Roger Sessions, Rudolph Serkin, and Aaron Copland. My copy is a hardbound volume with over 150 pages of music.

Even the standard composers are represented by very well-chosen pieces: there is Max Reger’s beautiful piece, Aus meinem Tagebuch Op. 82, book 1, no. 2, and Shostakovich’s exemplary PreludeOp. 34 no. 3 in G major, which condenses several of his compositional strategies from the period. Almost all the selections are good, which makes the minor composers’ pieces more interesting than usual. Examples here include at least two pieces by African-American composers: Evocation by Hale Smith (1925-2009), and The Cuckoo by Howard Swanson (1907-1978).

Not far into the book comes a pedagogic entry: a monograph (it’s hard to know what else to call it) by Wallingford Riegger, who was known for his advocacy of Schönberg’s style. The “monograph” is a series of Riegger’s own pieces, some fairly long, each prefaced by a half-page of description titled according to the technical content they exemplify: “The Augmented Triad,” “The Twelve Tones,” “Chromatics,” and so on:

Schönberg is also in the volume, immediately after Riegger’s “chapter,” and following a reproduction of Egon Schiele’s 1917 portrait. Significantly, Webern is placed at the very end of the book—implicitly, he’s the culmination of all 9 volumes of piano music. He is represented by the Variationen für Klavier Op. 27; “Variation” (i.e. movement) 3. (More on that piece elsewhere on this blog.)

Schönberg is also in the volume, immediately after Riegger’s “chapter,” and following a reproduction of Egon Schiele’s 1917 portrait. Significantly, Webern is placed at the very end of the book—implicitly, he’s the culmination of all 9 volumes of piano music. He is represented by the Variationen für Klavier Op. 27; “Variation” (i.e. movement) 3. (More on that piece elsewhere on this blog.)

Riegger’s contribution seems to have been specially commissioned by the editors, and it is unique, as far as I know, in music anthologies. It points up the volume’s ambitions to present modern music to a wide public—at least the public that plays piano at home—and in that sense it is a typically American initiative. It’s difficult to imagine such a thing in Germany, France, or other countries where the small audience for the avant-garde was taken as proper and not in need of remediation.

Yet despite Riegger’s long contribution, the Viennese school does not dominate. Stravinsky is represented by the entire Sonata and also the Tango, a total of 24 pages. American composers in this volume are mainly neoclassicists, and so on balance it’s American neoclassicism that represents average modernism, but the Vienna school that stands for modernism’s best moments.

1968

UE-Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts / Styles in 20th Century Piano Music, edited by Otto Karl Mathé.

This is an expanded version of the The UE Piano Book (1951); the editor says the book reflects “the various styles and manners of the piano music of our time: the dodecaphony of the Vienna School, neoclassicism, the folkloristic influence, educational music in its best sense and, finally, today’s avant-garde.” If we subtract “educational music,” because it is not a style, and “today’s avant-garde,” because it does not discriminate itself from the previous entries, we get three options for contemporary music: the Vienna school, neoclassicism, and “folkloric influence”—meaning music of the Soviet bloc.

This is an expanded version of the The UE Piano Book (1951); the editor says the book reflects “the various styles and manners of the piano music of our time: the dodecaphony of the Vienna School, neoclassicism, the folkloristic influence, educational music in its best sense and, finally, today’s avant-garde.” If we subtract “educational music,” because it is not a style, and “today’s avant-garde,” because it does not discriminate itself from the previous entries, we get three options for contemporary music: the Vienna school, neoclassicism, and “folkloric influence”—meaning music of the Soviet bloc.

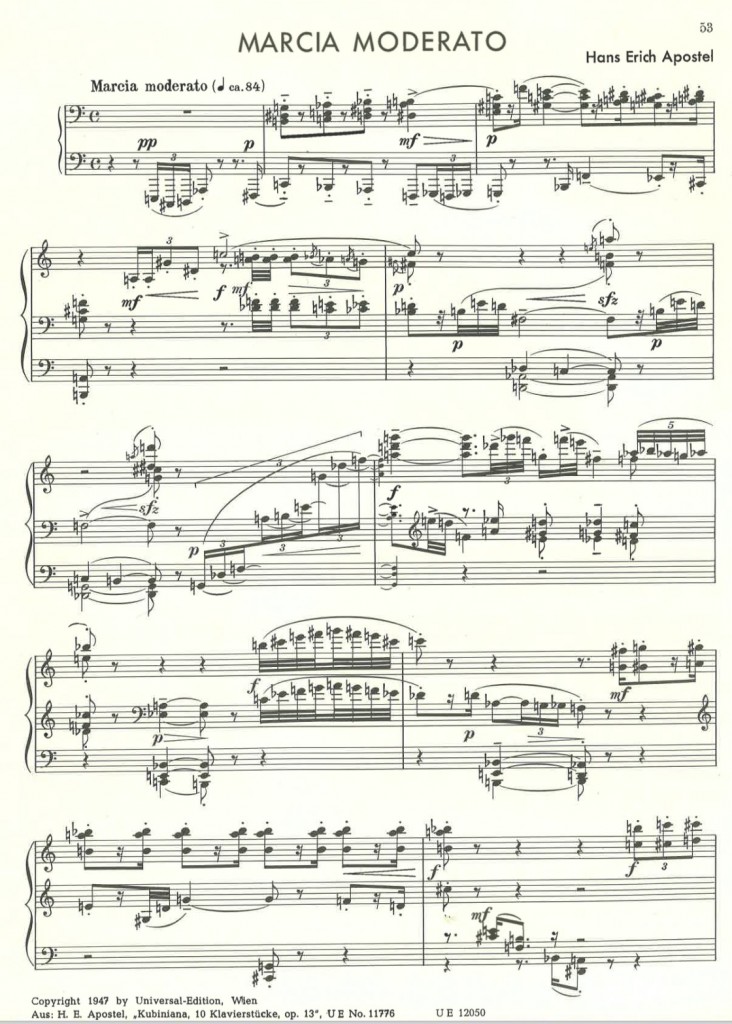

Max Reger, Richard Strauss, Alexander Tcherepnin, and Karol Szymanowski open the collection; they are presumably from the original 1951 edition. There is a generous selection of eastern European and Balkan material: Kodály, represented by the ubiquitous and uncharacteristic Klavierstück; Alois Hába; Felix Petyrek; and Bartók, represented by two pieces including the lengthy Night’s Music. All that becomes a preface, however, for what follows: an unprecedentedly large selection of Vienna school composers, including Schönberg, Joself Hauer’s Zwölftönspiel, Webern, Křenek, Wellesz, Hanns Jelinek, and Hans Erich Apostel.

All that was presumably in the original 1951 edition, which may therefore have been the most extensive collection of piano music from the Vienna school. From there the anthology drifts toward composers influenced by Prokofiev and Stravinsky, such as the Austrian opera composer Gottfried von Einem and the Swiss composers Willy Burkhard and Frank Martin. The French school is scarcely mentioned (there is one piece by Milhaud). The anthology continues with lesser-known composers in the general orbit of Vienna: the interesting Bulgarian composer Pantscho Wladigeroff (or Vladigerov, 1899-1978), the Belgian Marcel Poot (1901-1978), the Romanian Rudolf Wagner-Régeny (1903-1969), Boris Blacher (1903-1979), and the Italian Angelo Paccagnini (1930-1999).

All that was presumably in the original 1951 edition, which may therefore have been the most extensive collection of piano music from the Vienna school. From there the anthology drifts toward composers influenced by Prokofiev and Stravinsky, such as the Austrian opera composer Gottfried von Einem and the Swiss composers Willy Burkhard and Frank Martin. The French school is scarcely mentioned (there is one piece by Milhaud). The anthology continues with lesser-known composers in the general orbit of Vienna: the interesting Bulgarian composer Pantscho Wladigeroff (or Vladigerov, 1899-1978), the Belgian Marcel Poot (1901-1978), the Romanian Rudolf Wagner-Régeny (1903-1969), Boris Blacher (1903-1979), and the Italian Angelo Paccagnini (1930-1999).

And the collection—presumably in its expanded 1968 version—ends with Darmstadt: Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, Stockhausen, Henri Pousseur, and Boulez’s Sigle. It is hard to imagine a more doctrinaire anthology: this is the Museum of Modern Art of piano anthologies, didactic in its insistence on the Vienna school and Darmstadt, and inclusive only when its diversity fits the program.

1977

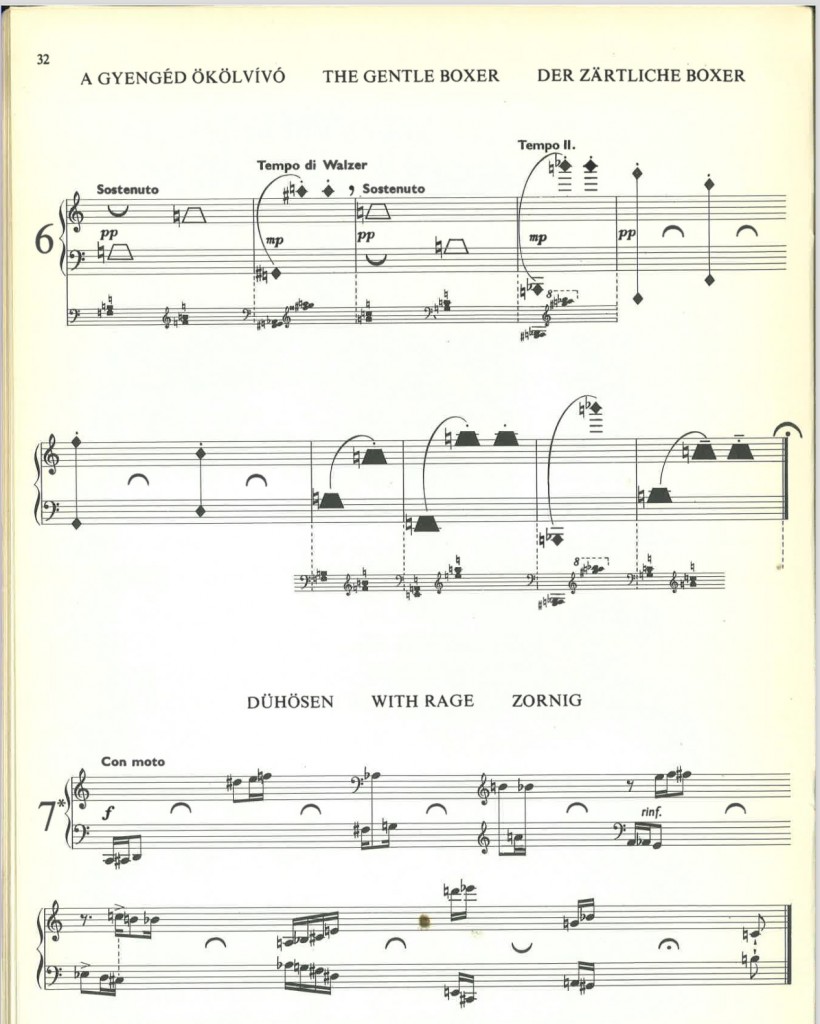

Tarka-Barka: A Microcosmic Collection of New and Extraordinary Pieces for Piano [by Hungarian composers], edited by Marianne Teöke (Editio Musica Budapest).

I would love to know more about this crazy anthology. It seems to be exclusively Hungarian composers from the 1970s who use non-conventional notation in their pieces.There is no introduction. The composers’ notational inventions are all listed together at the beginning, as if they shared them, but they don’t. Some are commonly used; the editor remarks of the rest “we would like them to become generally known.” The echo of Mikrokosmos in the title suggests a pedagogic initiative.

I would love to know more about this crazy anthology. It seems to be exclusively Hungarian composers from the 1970s who use non-conventional notation in their pieces.There is no introduction. The composers’ notational inventions are all listed together at the beginning, as if they shared them, but they don’t. Some are commonly used; the editor remarks of the rest “we would like them to become generally known.” The echo of Mikrokosmos in the title suggests a pedagogic initiative.

Many of the pieces are very short (a half-page, or less), and seem to be demonstrations of some notation or acoustical possibility. Except for Kurtág, the composers are very obscure: László Borsody, Attila Bozay (1939-1999), Lajor Huszár, Miklós Kocsár (b. 1933), György Kurtág (b. 1926), and Jószef Soproni. (See the Hungarian Composers site for some details.)

Many of the pieces are very short (a half-page, or less), and seem to be demonstrations of some notation or acoustical possibility. Except for Kurtág, the composers are very obscure: László Borsody, Attila Bozay (1939-1999), Lajor Huszár, Miklós Kocsár (b. 1933), György Kurtág (b. 1926), and Jószef Soproni. (See the Hungarian Composers site for some details.)

Few of the compositions could stand on their own. What was this all about? Did they all know one another? What prompted this collection, in 1977, in Budapest?

Few of the compositions could stand on their own. What was this all about? Did they all know one another? What prompted this collection, in 1977, in Budapest?

1978

Waltzes by 25 Contemporary Composers, edited by Robert Helps and Robert Moran (Peter, 1978)

1979

21 X 11: 12 Original Compositions Written by 11 Contemporary Composers, edited by Maurice Hinson (Hinshaw Music)

This is a populist anthology, mainly American neoclassicism and regionalism, with a sampling of Schönberg and Stravinsky. It’s odd to see two of Schönberg’s Six Little Pieces Op. 19 alongside unbearable nostalgic patriotic folksy pieces like Arthur Farwell’s Approach of the Thunder God (one of those pieces that seems to associate Native Americans, or at least the uncivilized Americas, with 4/4 drumbeats) and Ross Lee Finney’s Medley: Campfire on the Ice. The notion seems to have been to make the easiest possible nod to contemporary music—Hinson has even given a title to one of Stravinsky’s untitled pieces for children, calling it Siciliana—while also providing all the material for an unchallenging night at the piano.

Still, as usual, there are some interesting unusual pieces: Carlisle Floyd’s Night Song and Waltz are simple but subtle pieces done in imitation of Bartók and of modernist waltzes; Darius Milhaud’s Sorocaba, Karol Szymanowski’s Prelude in B Minor, and Vladimir Rebokov’s Dancing Demons are better than average set-pieces; and Virgil Thomson’s Homage to Marya Freund and to the Harp is a well-constructed blend of harp and piano sounds.

1981

20th Century Composers: Intermediate Piano Book (Peters, 1981)

1983 (ca.)

Das neue Klavierbuch, 3 vols. (Schott, c. 1983).

Here I continue my notes on Das neue Klavierbuch, which was first published as a single volume in 1948. (See above.)

In what is currently volume 3, after two pieces by Ligeti, all the succeeding pieces are copyrighted between 1980 and 1983. I assume this is the material used in the latest expansion, one that took Das neue Klavierbuch from 2 volumes to 3.

Assuming the additions begin with Hans-Werner Henze’s Ballade, there may be an intentional echo of Hindemith’s In einer Nacht that begins volume 3: both are serious, meditative pieces. Henze’s is marked “sehr Zart” (“very tender”) and Hindemith’s is subtitled “Phantastisches Duett zweier Bäume vor dem Fenster” (Fantastical duet of two branches in front of the window”). These two, in turn, recall Bartók’s Volkslied that opens volume 2: the entire collection evokes a kind of thoughtful, slow, dissonant modernism, relieved by modernist marches, mazurkas, and other dance pieces. It would be possible to play a selection from the three volumes as a kind of composition in its own right, in with slow movements alternating with scherzo-style fast movements.

This last volume also has some excellent unusual choices, such as Wilhem Killmayer‘s Nocturne III from An John Field (which I have not been able to find), the American composer Noël Lee‘s Intervalle, two pieces from Hans Werner Henze’s Sechs Stücke für junge Pianisten, and a lovely elegy by a lesser-known Romanian composer named Friedrich Wanek. The third volume, and the entire anthology, ends with two more obscure choices: Burlesque by the Bulgarian composer Emile Naoumoff (b. 1962), and Drei kleine Klavierstücke by Hans-Jürgen von Bose (b. 1953).

1994

UE-Klavieralbum für junge Pianisten: Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts, edited by Peter Roggenkamp (Universal Edition, 1994).

1996

The Century of Invention, edited by Maurice Hinson (European American Music Corporation / Schott, 1996).

2000

Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book (Boosey & Hawkes).

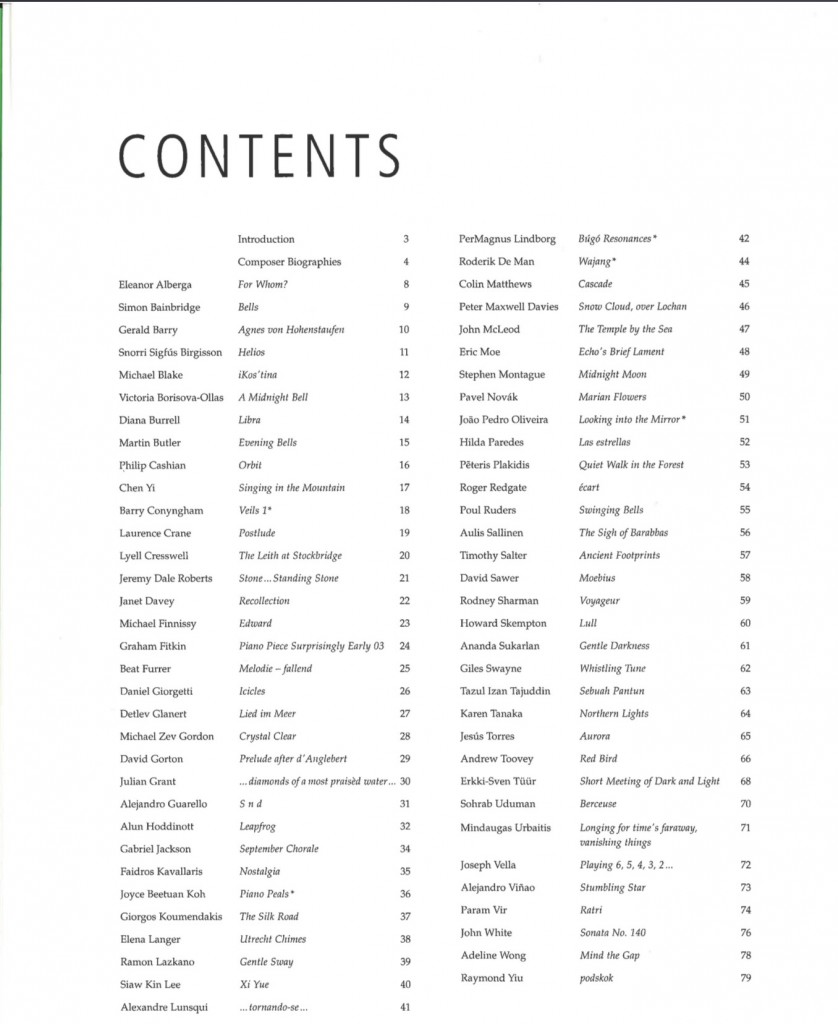

This is a collection of specially commissioned pieces, the “inspiration” (according to the prefatory letter by Franz Ohnesorg) of Ellen Taaffee Zwilich. It is intended to present playable work by important contemporary composers. Ohnesorg mentions some famously difficult modernist piano compositions by way of contrast: Boulez’s Second Sonata, Stockhausen’s Klavierstück series, “and, perhaps most out of reach, the incredible Ligeti Etudes.”

This is a collection of specially commissioned pieces, the “inspiration” (according to the prefatory letter by Franz Ohnesorg) of Ellen Taaffee Zwilich. It is intended to present playable work by important contemporary composers. Ohnesorg mentions some famously difficult modernist piano compositions by way of contrast: Boulez’s Second Sonata, Stockhausen’s Klavierstück series, “and, perhaps most out of reach, the incredible Ligeti Etudes.”

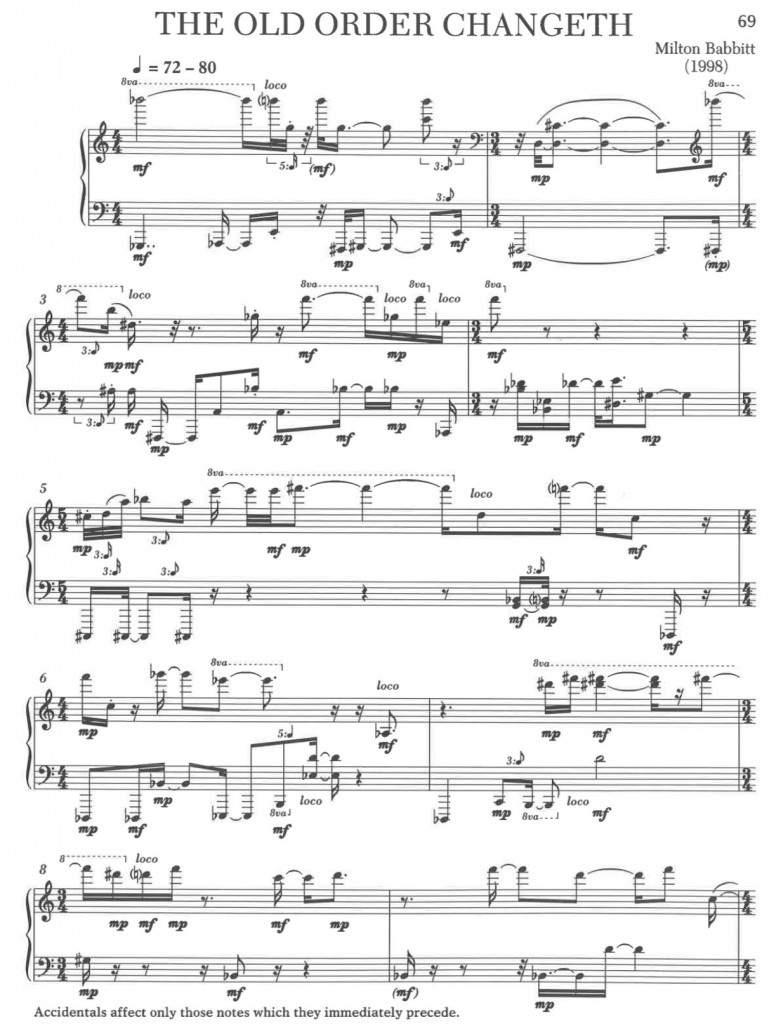

However not all the composers who were invited played along with the notion of keeping pieces within the reach of average pianists: Milton Babbitt is unapologetic in his composer’s notes, noting that his famously complex compositional strategies “decidedly [include] the present composition”; in her performer’s notes, Ursula Oppens remarks that Babbitt’s piece is “without a doubt the most difficult piece in this collection.” His piece, aggressively titled The Old Order Changeth, is a formidable challenge for a performer. Judging by the Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book, amateur piano playing is definitely a thing of the past: the book is almost an inadvertent manifesto against amateur involvement in music.

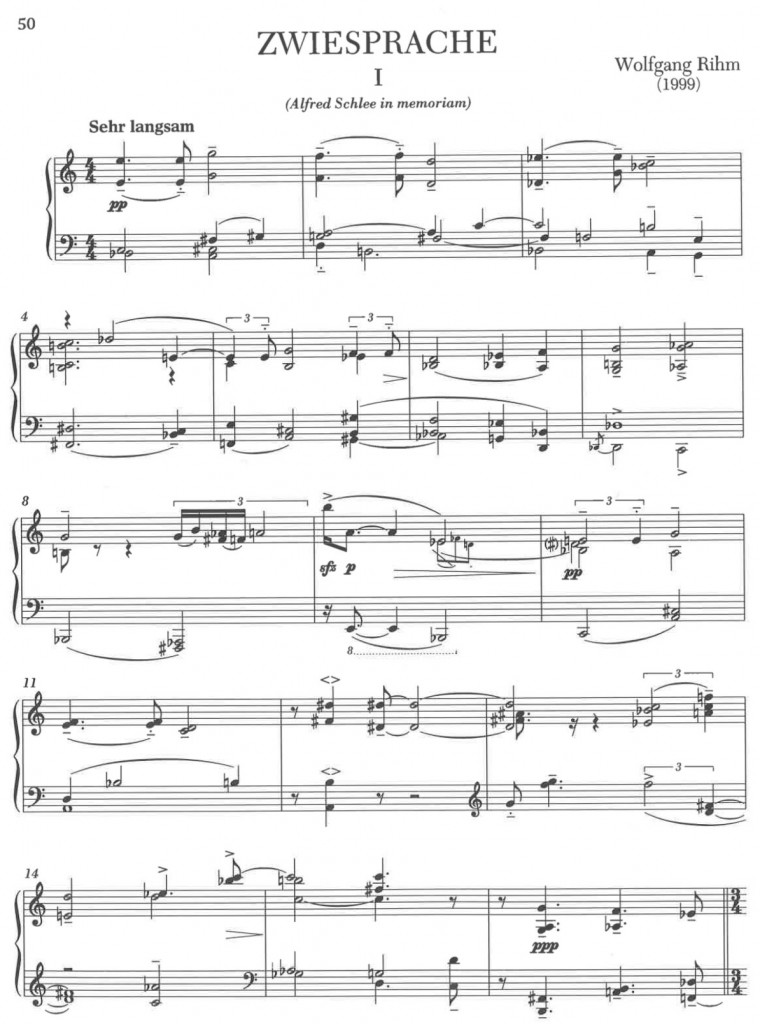

Having said that, I should note that not all the pieces are for advanced players only. There are some excellent easier pieces, for example John Harbison’s On an Unwritten Letter, Wolfgang Rihm‘s lovely Zweisprache, which is five slow pieces each in memoriam of a different person; and Louis Andriessen’s Image de Moreau.

Having said that, I should note that not all the pieces are for advanced players only. There are some excellent easier pieces, for example John Harbison’s On an Unwritten Letter, Wolfgang Rihm‘s lovely Zweisprache, which is five slow pieces each in memoriam of a different person; and Louis Andriessen’s Image de Moreau.

The ten composers included here are mostly safe, blue-chip choices. An exception is the composer identified only as Hannibal, whose work is stylistically out of range of the rest of the anthology. It’s an awkward moment, because it looks suspiciously like affirmative action or tokenism. Hannibal Lokumbe is a well-known jazz trumpeter, but an outlier in this collection that is otherwise narrowly dedicated to the North American high modernist tradition, influenced predominantly by Carter and Babbitt. It’s tempting to contrast the ill-advised addition of Hannibal with the more generous inclusion of African-Americans in the earlier International Library of Piano Music.

2001

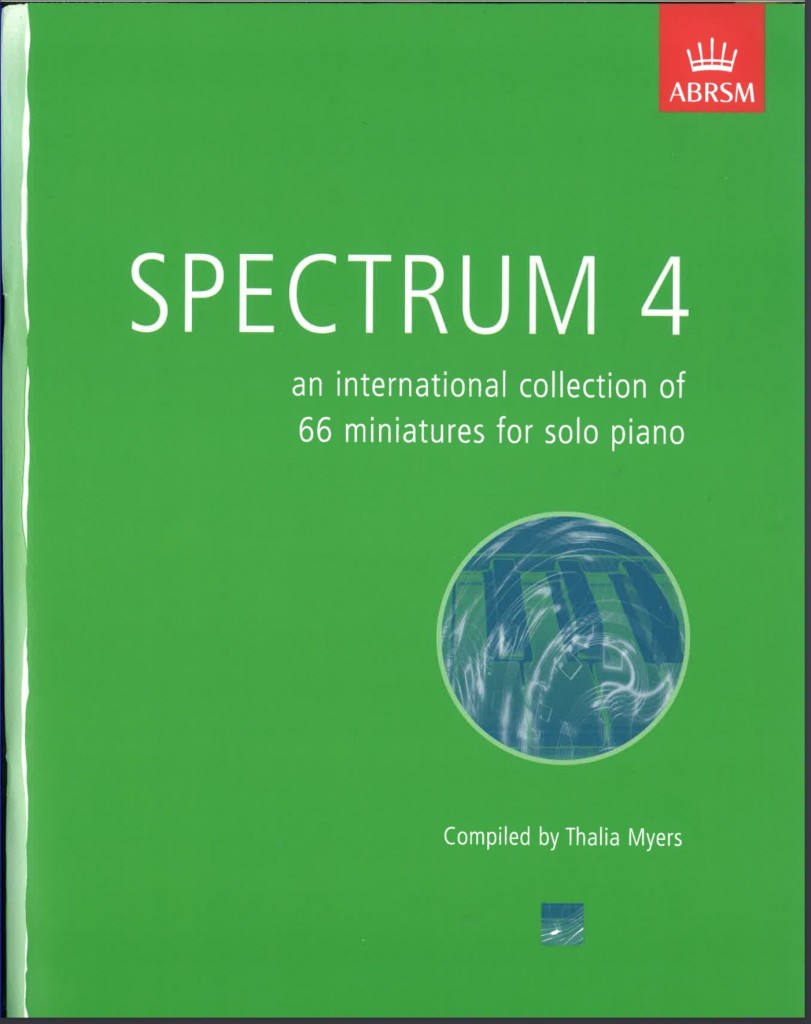

Spectrum: An International Collection of 25 Pieces for Solo Piano, edited by Thalia Myers, vols. 1-5 (Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, 2001 et seqq.)

This is a large collection, but it has an unusually high percentage of unrewarding pieces. Myers, the editor, describes the pieces as “miniatures”: they are mainly brief, and intended to be playable by average pianists. This initiative is one of several that attempt to return home piano playing to the role it had before modernism. (Another is the Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book, published the year before volume 1 of this series.) The risk is that many pieces are so much reduced from the composers’ usual styles that they lack interest.

A fairly high percentage of the pieces in these 5 volumes are minimalist, with a smaller number showing a wide variety of influences, from Boulez and Stockhausen and Carter to Nancarrow. The styles reflect the ages of the composers (many were born in the 1940s) and, presumably, Thalia Myers‘s choices (she was born in 1945).

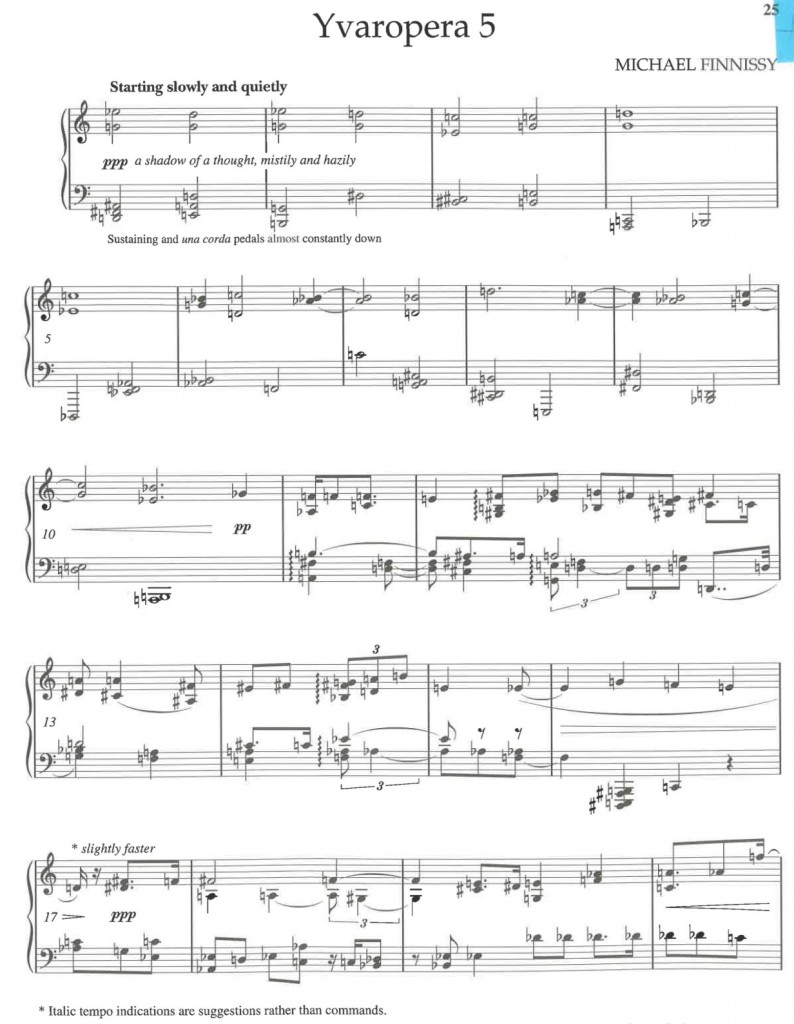

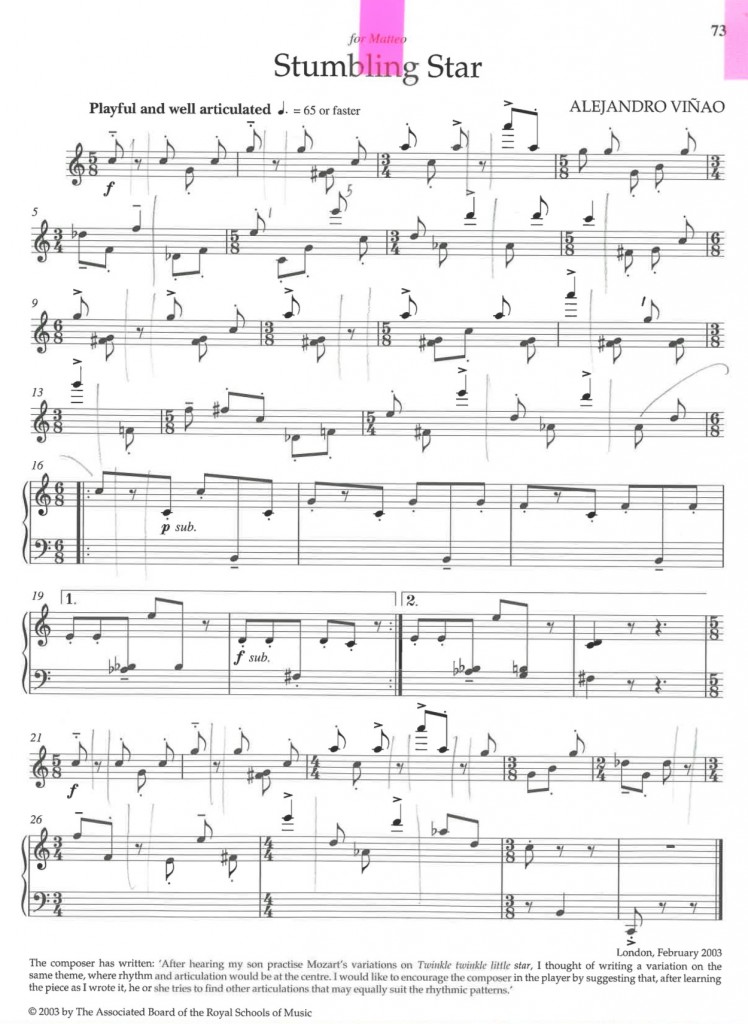

Volume 1 has some strong pieces in it: If the Silver Bird Could Speak by the the Jamaican composer Eleanor Alberga (b. 1949), a minimalist Toccata by David Bedford (1939-2011), Constellations by Diana Burrell (b. 1948), Michael Finnissy’s Yvaropera 5 (in which a 2.4 beginning devolves into some wonderfully subtle rhythms), Stephen Montague’s Mira (a simple minimalist piece based on shifting 6/8, 5/8, 4/8 rhythms), David Sawyer’s Diversion, and Howard Skempton’s Cantilena. The good pieces thin out, in my reading, in the later volumes: volume 2 has another Finnissy piece, Tango; volume 4 has several good pieces, including Alejandro Viñao’s Stumbling Star, an amusing piece inspired by his son’s playing of Mozart’s Twinkle twinkle little star.

2003

Anthology of 20th Century Piano Music: Intermediate to Early Advanced Work by 37 Composers, edited by Maurice Hinson (Alfred, 2003).

?

Neue Klaviermusik für Studium (Breitkopf). I have not yet seen this, so I am not sure of the editor or date.

2004

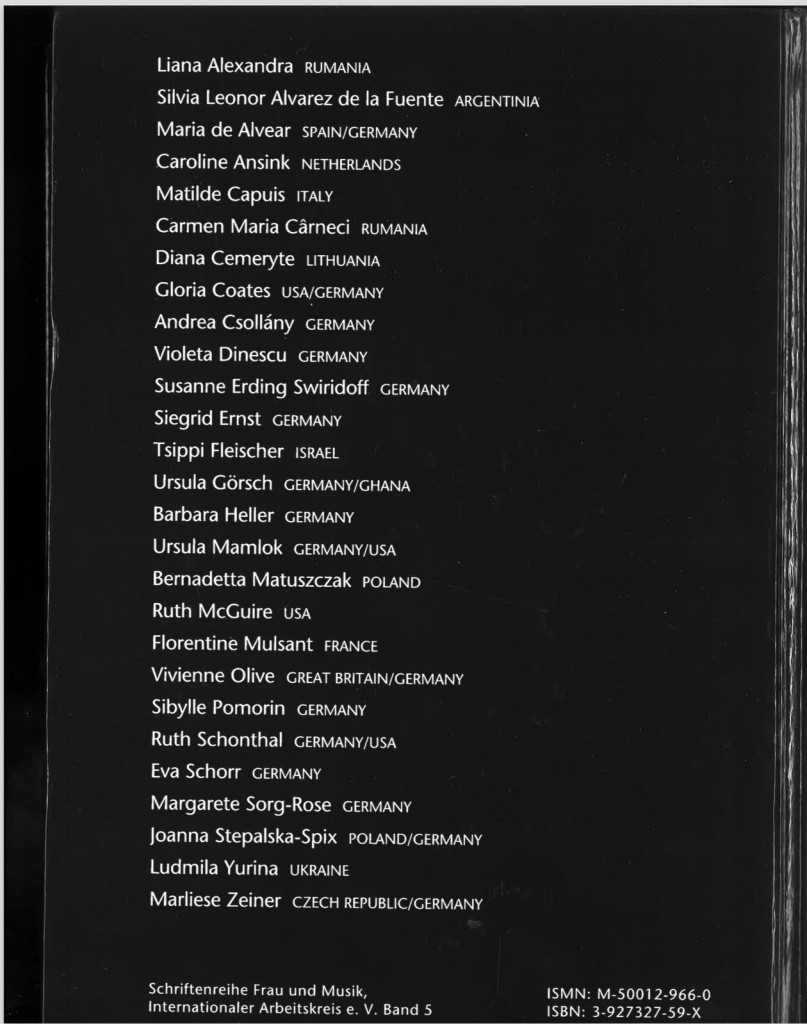

25 Plus Piano Solo: 25 Jahre Frau und Musik / 25 Years Women in Music, Jubiläumsausgabe (Internationaler Arbeitskreis Frau und Musik, Kassel).

This is a large, hardcover book with an international selection of women composers. It’s an amazingly good collection. Many are advanced compositions, but mainly still accessible for intermediate-level pianists. The overwhelming influence is Darmstadt, with traces of minimalism, Nancarrow, Carter, and others.

This is a large, hardcover book with an international selection of women composers. It’s an amazingly good collection. Many are advanced compositions, but mainly still accessible for intermediate-level pianists. The overwhelming influence is Darmstadt, with traces of minimalism, Nancarrow, Carter, and others.

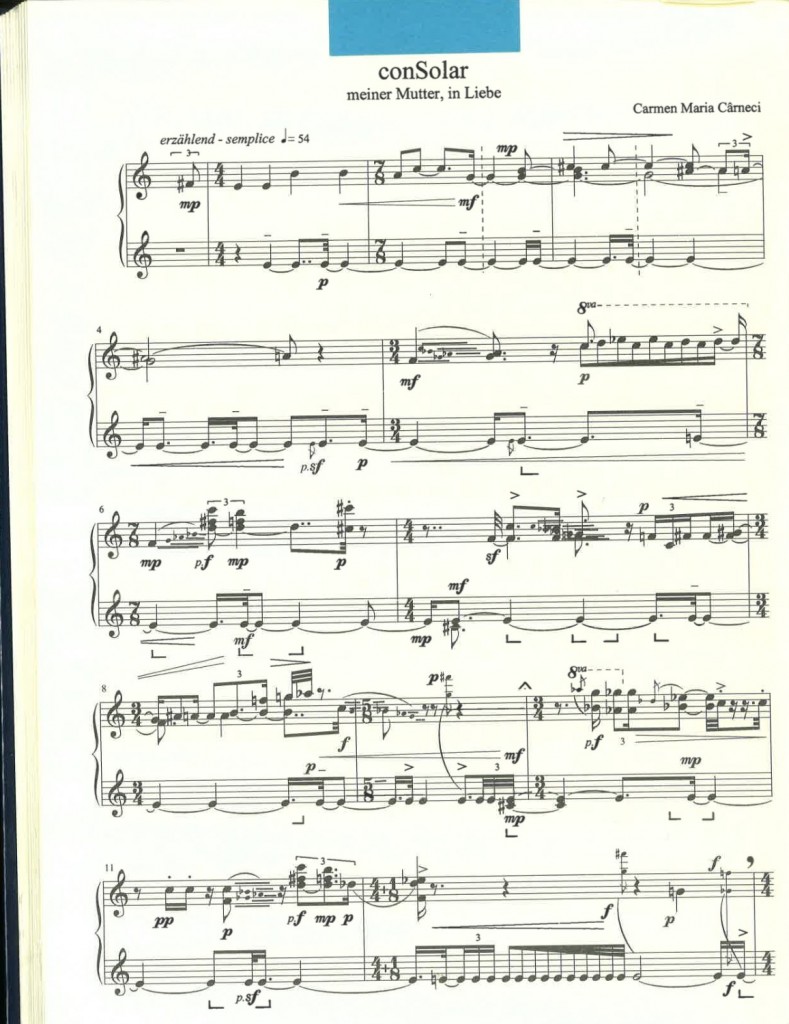

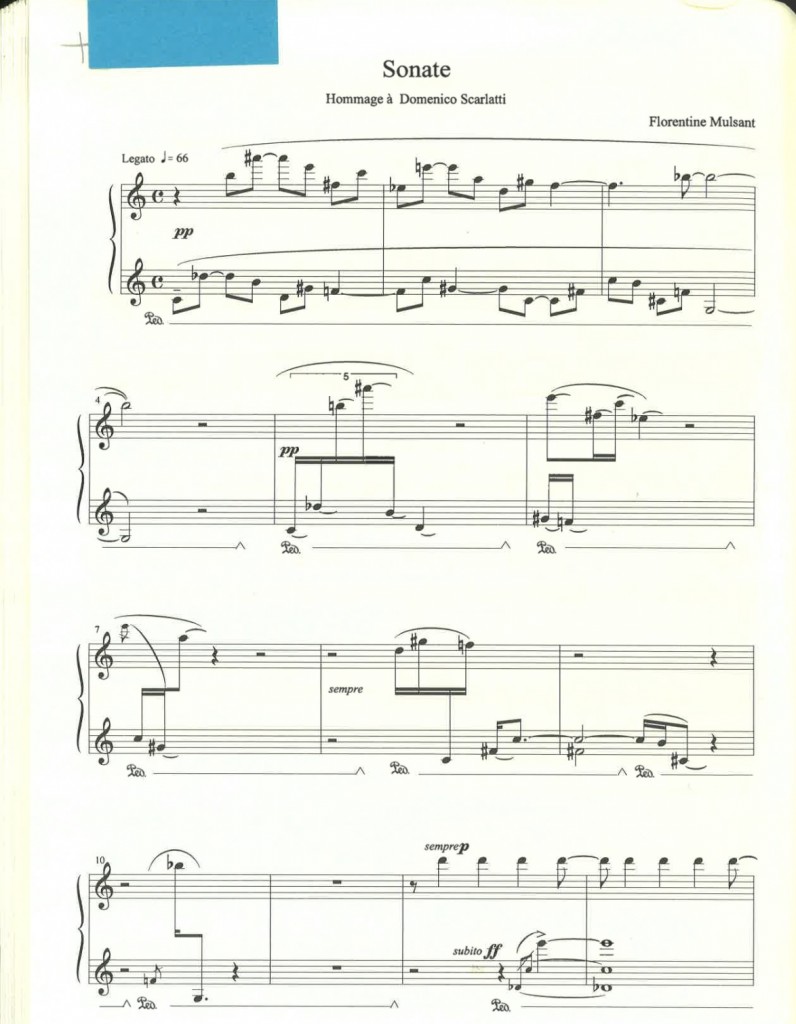

Among the excellent pieces is conSolar by Carmen Maria Cârneci (Romanina, b. 1957); Fünf lyrische Minaturen by Ruth McGuire (b. 1941, an American living in Vienna); and a Sonate, hommage à Domenico Scarlatti by Florentine Mulsant (b. 1962; she studied with Franco Donatoni).

Among the excellent pieces is conSolar by Carmen Maria Cârneci (Romanina, b. 1957); Fünf lyrische Minaturen by Ruth McGuire (b. 1941, an American living in Vienna); and a Sonate, hommage à Domenico Scarlatti by Florentine Mulsant (b. 1962; she studied with Franco Donatoni).

There is an excellent range of generations here, with one woman born in 1913, and another in 1974. Of all the anthologies I have seen that feature lesser-known composers, this is the most consistently excellent.

There is an excellent range of generations here, with one woman born in 1913, and another in 1974. Of all the anthologies I have seen that feature lesser-known composers, this is the most consistently excellent.

2009

Piano Album: Bärenreiter Contemporary Composers, edited by Michael Töpel (Bärenreiter, 2009).

This is another serious collection with little populist intention, smaller than the Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book but similar in the ambition of its editor.

2010

Contemporary Collage: Music of the 21st Century, edited by Helen Marlais, vol. 1, books 1-3 (FJH Music, 2010).

2011

13 Ways of Looking at the Goldberg: New Variations on the Goldberg Theme for Solo Piano, edited by Lara Downes.

This is discussed in another post.